When people (correctly) complain about Washington’s inefficiency and incompetence, I tell them that one of the problems is that the federal government is simply too big.

Indeed, this is the core message of my 7th Theorem of Government.

Simply stated, when politicians expand the size and scope of government, that increases the likelihood that there won’t be energy, expertise, or resources to address problems where government should play a role.

This is true in the United States. And it’s true in other nations.

That’s not merely me being an ideologue. There’s plenty of academic evidence showing that smaller governments are more competent.

Let’s expand on that argument. The U.K.-based Economist has an article that summarizes the insight of the 7th Theorem. Here are some excerpts.

You may sense that governments are not as competent as they once were. …A flagship plan to expand access to fast broadband for rural Americans has so far helped precisely no one. Britain’s National Health Service soaks up ever more money, and provides ever worse care. …

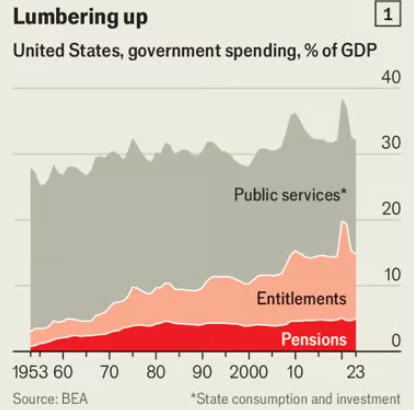

You may also have noticed that governments are bigger than they once were. Whereas in 1960 state spending across the rich world was equal to 30% of GDP, now it is above 40%. …All of which raises a paradox: if governments are so big, why are they so ineffective? The answer is that they have turned into what can be called “Lumbering Leviathans”. …governments have overseen an enormous expansion in spending on entitlements. …

On average across the OECD, social expenditure in countries with available data rose from 14% of GDP in 1980 to 21% in 2022. …Leviathans may not remain lumbering for ever. Running large deficits in order to fund transfer payments will, eventually, become too expensive—as countries such as Greece and Italy discovered in the 2010s.

I have two comments about the article.

First, I was initially tempted to simply write a column with a snarky title such as “Most Accurate Headline, Ever.”

Second, the article raises an important issue, but the Economist (as you might suspect) got some things wrong. It wants readers to think that the problem is that “redistribution is crowding out spending on other functions of government” and that politicians “fail to raise revenues.”

Since tax revenues are at or near record highs in almost all nations, there’s no need to waste any space on that issue.

With regards to the “crowding out” assertion, the Economist uses this chart of US data to claim that non-entitlement spending “has crashed” from 25 percent of GDP to 15 percent of GDP.

What the article doesn’t tell readers, however, is that this drop is mostly because defense budgets now consume a smaller share of economic output.

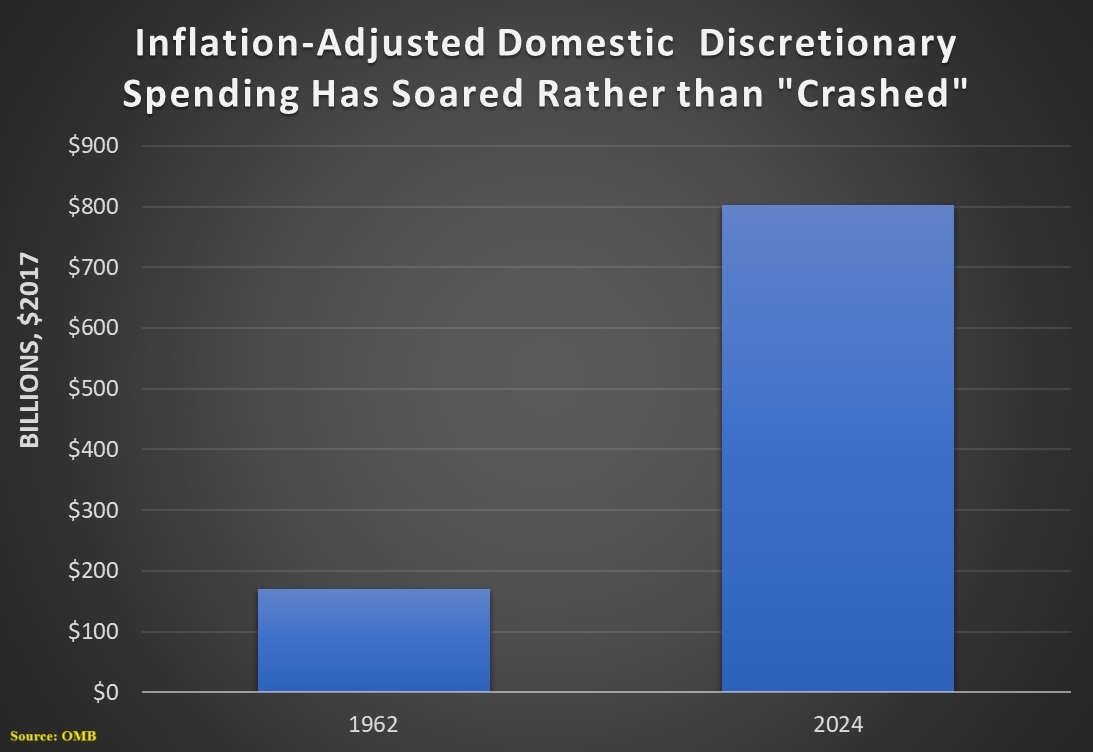

Moreover, the article fails to point out that inflation-adjusted non-entitlement spending has increased significantly.

The Office of Management and Budget has detailed data going back to 1962 for domestic discretionary spending. This is the type of spending (not Social Security or other entitlements) that has been slashed according to the article.

But here’s what actually happened. As you can see, outlays for this type of spending have jumped by more than 400 percent. And it would be an even bigger jump if we had data going back to the early 1950s.

If this is crashing, I hope my household budget crashes to the same degree.

On a more serious note, the article is correct in that United States (and other nations) have a major problem with entitlement spending.

But the Economist is wildly wrong when it argues that nations need more non-entitlement spending. What’s actually needed is rigorous spending caps.

No comments:

Post a Comment