By

Mary Grabar @ Real Clear Public Affairs

This essay is part of RealClearPublicAffairs's 1776 Series, which explains the major themes that define the American mind.

Recently,

Michael Barone heralded a bipartisan refutation of the

New York Times’s

1619 Project. As part of “an ongoing battle for control of the central narrative of American history,” Barone noted, the August 2019

Times magazine supplement had made the case for redefining the founding of the United States from

1776 to 1619, when,

presumably, the first slave ship came to Virginia, beginning a chain of exploitation by which the country supposedly built her wealth.

Barone notes how

Sean Wilentz, writing in the liberal

Atlantic, made “mincemeat” of lead writer Nikole Hannah-Jones’

contention

that “protecting slavery was the main motive of the American

Revolution.” With distinguished historians James McPherson, James Oakes,

Victoria Bynum, and Gordon Wood, Wilentz also

co-signed a letter to the

Times “lamenting” the Project’s “factual errors.” The

National Association of Scholars,

Law & Liberty, and

World Socialist also published effective rebuttals.

Racism and fascism, Zinn argued, were in America’s very “bones”—a charge echoed by

the 1619 Project’s claim about racism being in “our DNA.”

And yet, the 1619 Project is being taught in schools. The Project writers’ success in getting their

materials adopted owes a considerable debt to Howard Zinn’s

A People’s History of the United States, first published in 1980 and also used widely in classrooms

. Zinn, too, draws attention to that ship approaching Jamestown, quoting

at length from an imaginative reconstruction in order to introduce the idea that “There is not a country in world history in which racism has been so important, for so long a time, as the United States.” Racism and fascism, Zinn argued, were in America’s very “bones”—a charge echoed by the 1619 Project’s claim about racism being in “our DNA.” For Zinn, the idea of a

United States was a “myth,” and the nation itself was a “pretense.” Hannah-Jones even claims Zinn’s motto of “bottom-up” history as her own invention.

Zinn advanced Communist Party USA

Chairman William Z. Foster’s interpretation of American history as an

Edenic land subjugated by greedy capitalists, which Foster had

articulated in his 1951

Outline Political History of the Americas.

Both Zinn and Foster trace every bloody event—Indian massacres,

slavery, wars, riots, factory fires—to capitalism. The simplistic

explanation captivates readers. For many, Georgetown University

professor

Michael Kazin notes,

A People’s History

carries “the force and authority of revelation,” such that readers

believe that they have gotten all the American history they will ever

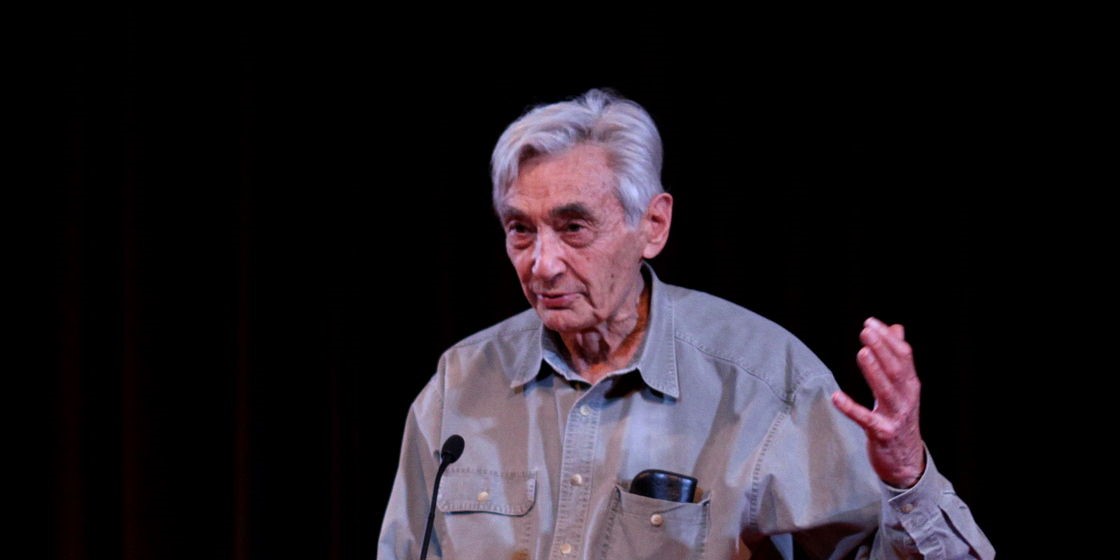

need. Zinn especially captivates adolescents and Hollywood actors—most

of whom, as

Ricky Gervais

quipped, have a Greta Thunberg-level knowledge of history. Zinn himself

became a wealthy celebrity, and he received tributes from rockers and

movie stars when he died in 2010 at the age of 87.

Zinn was asked to write the book after

he had made headlines as a professor butting heads with his college

president, Boston University’s John Silber. Earlier, he had been

fired

for insubordination by Spelman College president Albert Manley. Zinn

led students on civil rights and anti-Vietnam War protests, helped

hide the stolen

Pentagon Papers, testified at Daniel Ellsberg’s trial,

brought home three American POWs from North Vietnam in a propaganda ploy, and lectured in France, Italy, Japan, and South Africa.

In writing Debunking Howard Zinn,

I read many of Zinn’s sources and found egregious plagiarism, . . .

deletion of critical information, deliberate misrepresentation of

sources, and invention of facts.

But Zinn did not do real history—that

is, scholarship that builds on the work of previous historians, gives

accurate and detailed information, and presents a balanced view.

A People’s History,

like the 1619 Project, drew criticism from historians on the left and

right. Kazin felt that it shortchanged progressive accomplishments like

labor laws and civil rights; Harvard professor

Oscar Handlin called it a “fairy tale.” Still, the book kept selling, and sales total about three million today.

In writing Debunking Howard Zinn,

I read many of Zinn’s sources and found egregious plagiarism (usually

from New Left historians and socialist non-historians, like Hans

Koning), deletion of critical information, deliberate misrepresentation

of sources, and invention of facts. Zinn used his status as a professor

to discredit other historians. He attacked Gordon Wood’s mentor,

Bernard Bailyn, whose name appears on many of Zinn’s lecture notes.

Zinn’s devotee, Matt Damon, who grew up next door to the Zinns in

Cambridge, Massachusetts, championed Zinn’s book and mocked Wood in his

1997 blockbuster movie, Good Will Hunting.

Zinn targeted the most accomplished

historians, mainly associated with Harvard University, and winners of

multiple prizes, such as the Bancroft and the Pulitzer. They include

Samuel Eliot Morison (an expert on Columbus) and Bailyn (an expert on

the Founding). Zinn charged such historians with complicity in promoting

a false history of the United States.

The first five-and-a-half pages of A People’s History were largely plagiarized from Koning’s paperback for high school students, Columbus: His Enterprise: Exploding the Myth,

and exaggerate Koning’s own distortions of Columbus. Zinn also attacks

Morison, accusing him of burying the truth about “genocide.”

To preempt criticism, Zinn presents an

analogy of the historian as mapmaker, who “must first flatten and

distort the shape of the earth,” then choose from “the bewildering mass

of geographic information” for the “particular map.” He must consider

“contending interests” and emphasize certain facts over others. So

Morison makes an “ideological choice” by telling “ a grand romance”

about Columbus, whose “’defects,’” in Morison’s words, “were largely . .

. of the qualities that made him great—his indomitable will, his superb

faith in God, and in his own mission to be the Christ-bearer to lands

beyond the seas.” Traditional historiography like Morison’s promotes

“the quiet acceptance of conquest and murder,” Zinn believed, as “the

past is told from the point of view of governments, conquerors,

diplomats, leaders. . . . as if they, like Columbus, deserve universal

acceptance, as if they—the Founding Fathers, Jackson, Lincoln, Wilson,

Roosevelt, Kennedy, the leading members of Congress, the famous Justices

of the Supreme Court—represent the nation as a whole.”

"The Founding Fathers were mortals, not gods; they could not overcome their own

limitations and the complexities of life that kept them from realizing their ideals."

In the People’s History chapter “A Kind of Revolution,” Zinn attacks Bailyn’s essay “The Central Themes of the American Revolution: An Interpretation,” published in the 1973 collection Essays on the American Revolution.

“To say, as one historian (Bernard Bailyn) has done recently, that ‘the

destruction of privilege and the creation of a political system that

demanded of its leaders the responsible and humane use of power were

their highest aspirations’ is to ignore what really happened in the

America of these Founding Fathers.”

Yet the source of this quotation,

Bailyn’s own concluding paragraph, addresses Zinn’s criticism. Preceding

the Bailyn sentence that Zinn quotes is this one: “The Founding Fathers

were mortals, not gods; they could not overcome their own limitations

and the complexities of life that kept them from realizing their

ideals.” Bailyn goes on: “To note that the struggle to achieve these

goals is still part of our lives—that it is indeed the very essence of

the politics of our time—is only to say that the American Revolution, a

unique product of the eighteenth century, is still in process, in this

bicentennial age. It will continue to be, so long as men seek to create a

just and free society.” Bailyn did not ignore “what really happened in

the America of these Founding Fathers,” as Zinn claims.

Zinn also targets a passage from Bailyn’s The Ideological Origins of the American Revolution

(1967): “Everyone knew the basic prescription for a wise and just

government. It was so to balance the contending powers in society that

no one power could overwhelm the others and, unchecked, destroy the

liberties that belonged to all. The problem was how to arrange the

institutions of government so that this balance could be achieved.” The

passage appears in the context of Bailyn’s explanation of a quotation

from John Adams’s 1776 pamphlet, Thoughts on Government, in

which Adams comments on the colonists’ opportunity “to form and

establish the wisest and happiest government that human wisdom can

contrive.” Bailyn himself asks, “how fair . . . was the opportunity?” in

order to introduce the “basic prescription,” i.e., “England’s ‘mixed’

government”—which offered the aristocracy and nobility as safeguards

against anarchy and mob rule.

After quoting this deceptively selected passage, Zinn ignores what Bailyn writes—and

asks: “Were the Founding Fathers wise and just men trying to achieve a

good balance?” He answers: “In fact, they did not want a balance, except

one which kept things as they were, a balance among the dominant forces

at that time. They certainly did not want an equal balance between

slaves and masters, propertyless and property holders, Indians and

white.”

Zinn charges that both the Declaration of Independence and its inspiration, Locke’s Second Treatise of Government,

“talked about government and political rights, but ignored the existing

inequalities in property,” and asks, “And how could people truly have

equal rights, with stark differences in wealth?”

Zinn’s ad hominem attacks on John

Locke, whose ideas he wrongly presents as being accepted wholesale by

the Founders, focus on the philosopher’s wealth. And besides, Locke’s

“nice phrases about representative government” were betrayed by the

reality in England, after the Revolution he had advocated had taken

place: “At the very time the American scene was becoming tense, in 1768,

England was racked by riots and strikes—of coal heavers, saw mill

workers, hatters, weavers, sailors—because of the high price of bread

and the miserable wages.” In the American colonies, Zinn notes, “the

reality behind the words of the Declaration of Independence” was that “a

rising class of important people needed to enlist on their side enough

Americans to defeat England, without disturbing too much the relations

of wealth and power.”

No wonder Zinn does not want his readers to read Bailyn, who quotes from a

1776 pamphlet:

“no reflection ought to be made on any man on account of birth,

provided that his manners rises decently with his circumstances, and

that he affects not to forget the level he came from.” Nor would Zinn

want readers to be exposed to the belief expressed in 1774 that “lawful

rulers are the servants of the people” who exhibit “wisdom, knowledge,

prudence,” and “Godliness.”

Contrary to Zinn’s

insinuations, Bailyn thoughtfully explores how the "presence of an

enslaved Negro population in America inevitably became a political issue

where slavery had [the] general meaning [of political oppression]."

Contrary to Zinn’s insinuations,

Bailyn thoughtfully explores how the “presence of an enslaved Negro

population in America inevitably became a political issue where slavery

had [the] general meaning [of political oppression].” Furthermore,

“[t]he contrast between what political leaders in the colonies sought

for themselves and what they imposed on, or at least tolerated in,

others became too glaring to be ignored.” Bailyn cites the increasing

number and intensity of arguments from James Otis, Reverend Stephen

Johnson, Richard Wells, John Allen, and John Mein, including a

“jeremiad” by Levi Hart refuting Locke with Biblical appeals, along with

the measures taken against the slave trade by several northern states.

Bailyn’s mountains of evidence show that a new kind of social system and

government offered a way out of the conditions in England that led to

“riots and strikes” and the injustices of slavery.

Zinn’s attacks on the nation’s most

respected historians, however, seemed to increase the book’s popularity.

By 1992, 300,000 copies of

A People’s History of the United States had been sold, and a second, expanded edition was published in 1995. It got another boost in

Good Will Hunting,

written by Damon and co-star Ben Affleck. When Zinn’s book came out in

1980, Damon was an impressionable ten-year-old. Seventeen years later,

he played the titular star, a 20-year-old victim of child sexual

abuse—and a genius working as a janitor at MIT.

Zinn probably helped write a key

scene. It begins with a barroom debate with a Harvard graduate student

about other historians. Will pegs the Harvard student as a “first-year

grad student” who has “just finished some Marxian historian, Pete

Garrison prob’ly,” whose ideas will convince him for a month, whereupon

he will “get to James Lemon” and become enthralled with “how the

economies of Virginia and Pennsylvania were strongly entrepreneurial and

capitalist back in 1740.” But by “next year,” the genius predicts, he

will be “regurgitating Gordon Wood, about . . . the pre-revolutionary

utopia and the capital-forming effect of military mobilization.” In

response, the grad student presumably quotes from Daniel Vickers’s

Farmers and Fishermen: Two Centuries of Work in Essex County, Massachusetts, 1630-1850,

but Will completes the sentence, saying, “Wood drastically

underestimates the impact of social distinctions ‘predicated upon

wealth, especially inherited wealth.’ You got that from Vickers’ ‘Work

in Essex County,’ page 98, right? Yeah, I read that, too.” The

rapid-fire rebuke suggests that the nation’s oldest and most respected

university serves the rich, while real geniuses are relegated to

janitorial work. It’s class warfare on the big screen.

The information in this exchange comes from one essay, “

Inventing American Capitalism,” by Wood in a journal Zinn read and notated,

The New York Review of Books.

Wood includes a passing reference to Lemon as co-leader of a post-World

War II change in perspective about the shift among colonial

farmers—from “mere subsistence agriculture” to entrepreneurial

production of “surpluses for markets.” Marx’s theory about “the

transition from feudalism to capitalism” did not apply, Wood wrote,

because, while in England large landowners employed tenant farmers,

American farmers, cultivating their own land, were motivated to produce

surplus.

In a later exchange with Lemon, Wood conceded that, yes, “many

social and other distinctions” existed “among the so-called common

people,” but made clear that “those distinctions were less important

than the commonality of ordinary people, that is, the common working

people (the producers) as distinguished from those who in the eighteenth

century were labeled leisured gentlemen (the consumers).” The “blurring

and transformation of this age-old distinction . . . lay at the heart

of the democratic revolutions of the late eighteenth century, the

American version of which was carried further than elsewhere.” One can

see, then, why Wood would be targeted in a movie praising

A People’s History, which presents the middle class as gulled by the “language of freedom” by “a government of the rich and powerful.”

Two generations

have come of age believing Zinn’s fraudulent history. . . . As I’ve

discovered while giving talks, his followers refuse to consider

countervailing evidence.

The cinematic fantasy of a bar-hopping

20-year-old outwitting the best historians is repeated in a later

scene, when Will Hunting scans the books in his psychiatrist’s office.

He reads, “

A History of the United States, Volume I,” with

tough-guy skepticism and tells the psychiatrist that if he wants to read

a “real” history book he should read “Howard Zinn’s

A People’s History of the United States.

That book will knock you on your ass.” Thus, the movie repeats Zinn’s

own claim that his book is the alpha and omega of history writing.

Two generations have come of age

believing Zinn’s fraudulent history. Zinn has become a sainted figure,

and his book has even been used as a

sacred object on which to take

oaths of office. As I’ve discovered while giving talks, his followers refuse to consider countervailing evidence.

By contrast, Wood’s tribute to Bailyn, “

Reassessing Bernard Bailyn’s The Ideological Origins of the American Revolution on the Occasion of Its Jubilee,”

is a hallmark of scholarship. Wood builds upon Bailyn’s research and

ends with a plea for continuing the work. The current academic trends,

Wood predicts, will leave a “popular hunger for impartial and balanced

histories of the nation’s origins” for “non-academic historians” to

fulfill. “Politicized monographs,” meanwhile, will “lie moldering in

university libraries,” to be read, “if they are read at all, only by

other scholars.”

If only this were so. The 1619 Project suggests otherwise.

A People’s History

and the 1619 Project not only teach a false history but also make

students cynical about their country, about historical truth, and about

the possibility of reasoned debate.

Another of Bailyn’s mentors, Oscar Handlin, practically invented immigration history. In responding to his critical review of

A People’s History,

Zinn accused Handlin of political bias. But Handlin, of similar

Russian-Jewish immigrant background as Zinn, enjoyed the opportunities

offered him in our oldest and most revered institutions of higher

learning, where barriers against Jews came down. Handlin’s career is a

testament to the improved realization of our country’s founding

principles.

Traditional history writing is meritocratic. It values learning from the past and engaging in fair debate. A People’s History and the 1619 Project not only teach a false history but also make students cynical about their country, about historical truth, and about the possibility of reasoned debate.

History must be reclaimed from its new aristocracy of ideological

scholars, who see the past only as a battlefield of ideological, ethnic,

racial, and sexual conflict. This approach, which Howard Zinn did much

to advance, has been distressingly successful in misleading young people

in the United States.

Mary Grabar earned her Ph.D. in

English from the University of Georgia in 2002, after working in

advertising and as a free-lance writer. While holding a series of

positions as an instructor, the last in the Program in American

Democracy and Citizenship at Emory University, she wrote articles about

the corruption of education, including by Howard Zinn, and founded the

nonprofit Dissident Prof Education Project (dissidentprof.com). In 2014, she became a resident fellow at the Alexander Hamilton Institute for the Study of Western Civilization

in Clinton, New York, where she continued her research on a biography

of the late black conservative writer, George Schuyler. In 2017, she

began writing Debunking Howard Zinn: Exposing the Fake History That Turned a Generation against America, which was published in August 2019.

This essay may be republished for free with attribution. (These terms do not apply to outside articles linked on the site.)

Mary Grabar earned her Ph.D. in

English from the University of Georgia in 2002, after working in

advertising and as a free-lance writer. While holding a series of

positions as an instructor, the last in the Program in American

Democracy and Citizenship at Emory University, she wrote articles about

the corruption of education, including by Howard Zinn, and founded the

nonprofit Dissident Prof Education Project (dissidentprof.com). In 2014, she became a resident fellow at the Alexander Hamilton Institute for the Study of Western Civilization

in Clinton, New York, where she continued her research on a biography

of the late black conservative writer, George Schuyler. In 2017, she

began writing Debunking Howard Zinn: Exposing the Fake History That Turned a Generation against America, which was published in August 2019.

This essay may be republished for free with attribution. (These terms do not apply to outside articles linked on the site.)