n Part I of this series about six months ago, I wrote that “I favor ‘freedom conservatism‘ over ‘national conservatism‘ because the former is unambiguously based on liberty and the latter veers toward populism.”

And I defined a populist as “someone who exploits economic ignorance to push policies that sound appealing to voters in the short run (such as protectionism, industrial policy, or class warfare) but do economic damage in the long run.”

That column then looked at some academic research showing that populist policies lead to less economic growth.

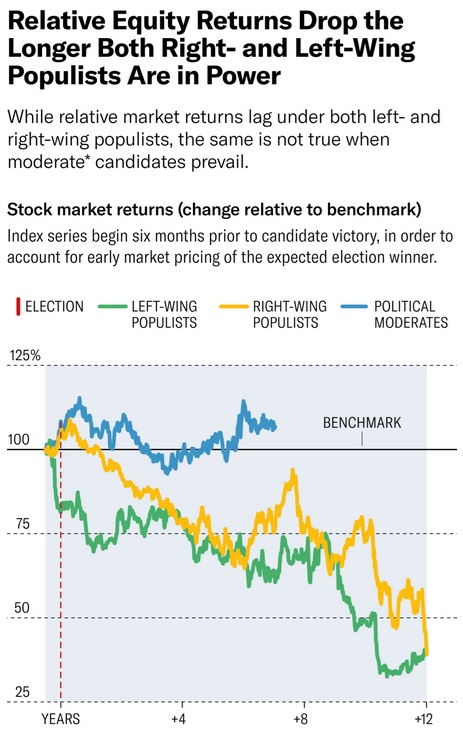

Today, let’s look at more evidence, starting with this chart showing that financial markets do worse under populist rule.

The chart comes from a study recently published by the Harvard Business Review. Authored by Roberto Stefan Foa Rachel Kleinfeld, it measure the impact of populist policies on economic outcomes.

Here are some of the highlights.

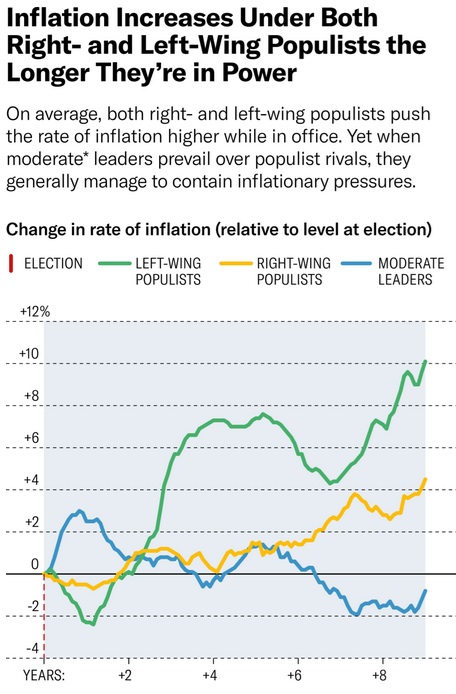

…we reviewed daily stock market data from Refinitiv comparing total returns (in U.S. dollars, including dividends) for all countries for which we have data (developed and major emerging markets), to see how markets performed under left and right-wing populists… Beyond the headline effects on economic growth, the authors also estimate that 15 years of populist rule leaves national debt up to 10% higher than otherwise, with inflationary pressures as a result. We examined this effect using monthly consumer price data from the World Bank’s Global Database of Inflation to see how price indices change from the moment populists enter office up until 12 months after their departure, thereby capturing lagging effects. On average, left-wing populists see inflation rise within two to four years. Right-leaning populists start out better, but produce a similar result by the end of their second term.

Here are the aforementioned inflation results.

The unavoidable conclusion is that populists like printing money.

The study notes that populists represent “public choice” in action.

In other words, politicians who are motivated by personal ambition rather than national interest (as noted in my Nineteenth Theorem of Government).

Whether a populist claims to be of the left or the right, they tend to value short-term gains over long-term results. Taken together, the evidence suggests a common result: rising levels of debt and inflation, and sub-standard performance for markets and growth. …thinking of populists as left or right is a misunderstanding. Populists care little about ideology — what they want is power.

I’ll close by sharing the methodology the authors used to identify populist governments.

“Populists” were identified using criteria widespread in political science and based on external projects we have advised. Populists in this criteria are defined by three factors: 1) they center a political strategy that divides their population between a good and righteous “people” and an elite or undeserving minority; 2) they claim that they are the sole or best representative of “the people,” and 3), they define democracy as requiring that the government serve the will of “the people” and do not accept constraints from independent institutions, oversight, or inalienable rights.

The article does not list specific populist governments, but there is a link to another report that lists 46 different governments from 1990-2018.

As you might suspect, Trump is listed as a populist. I have no objection to that characterization, as you can see from this 2016 column, but I wonder why class-warfare politicians like Obama are not also on this list. Targeting a narrow slice of the population (the top 1 percent or top 10 percent) with political vitriol and reckless policy should be viewed as pure populism.

Same for Kamala Harris, especially when you consider her views on other issues such as price controls, entitlements, handouts, equality of outcomes, and rent subsidies.

No comments:

Post a Comment