In February, a stream of tractors driven by Italian farmers arrived

at the outskirts of Rome, horns blaring. The scene, which was captured by

the Agence France-Presse, was just one of dozens of protests across

Europe against EU regulations that farmers said threatened to put them

out of work.

“They’re drowning us with all these regulations,” one farmer at a protest in Pamplona, Spain, told The Guardian. “They need to ease up on all the directives and bureaucracy.”

Dutch lawmakers responded in 2022 by passing legislation that

required farms near nature reserves to slash nitrogen emissions by 70

percent.

The policy was part of the government’s plan to sharply reduce

livestock farming in Europe. The thinking was that since the livestock

sector contributes to about a third of all nitrogen emissions globally,

the government would have to target farmers to meet its goal to cut

nitrogen emissions in half by 2030.

When asked by a reporter in 2023 whether he thought he would be able

to pass his farm on to his children, one Dutch farmer struggled to

speak.

“No,” he said tearfully. “No.”

Farmers are not the only ones unhappy with Brussels’s aggressive war on climate change.

Whether this retreat stemmed from concerns that these environmental

regulations would cause serious harm to the economy (and European

farmers), or from concern that the Green agenda would lead to a

bloodbath at the ballot box, is unclear.

Whatever the case, the reversal didn’t prevent a historic defeat for Green parties in June’s European Parliament elections, which saw them lose a third of their seats.

“There is no sugarcoating it,” the New York Times lamented following the June elections, “the Greens tanked.”

Political scientist Ruy Teixeira described the event as a “Greenlash.”

“In Germany, the core country of the European green movement, support

for the Greens plunged from 20.5 percent in 2019 to 12 percent,”

Teixeira, a scholar at the American Enterprise Institute, noted.

He continued:

Shockingly, among voters under 25, the German Greens actually did

worse than the hard right Alternative for Germany (AfD). That contrasts

with the 2019 elections, when the Greens did seven times better than the

AfD among these young voters.

And in France, Green support crashed from 13.5 percent to 5.5

percent. The latter figure is barely above the required threshold for

party representation in the French delegation.

Bans Against Hot Showers and Swimming Pools?

Pundits across the world are still trying to figure out why Green parties crashed so hard, which leads one to wonder if they were paying attention.

It wasn’t just crackdowns on farming. Facing an energy crisis, governments across Europe began to roll out regulations forcing Europeans to adopt, shall we say, more spartan lifestyles.

“Cold swimming pools, chillier offices, and shorter showers are the new normal for Europeans,” Business Insider reported, “as governments crack down on energy use ahead of winter to prevent shortages.”

In other words, instead of producing or purchasing more energy, governments began to crack down on energy consumption.

It didn’t stop there.

In May 2023, months after Germany shut down its last three remaining nuclear power plants, the Financial Times reported

that many Germans were “outraged and furious” at a law that forced them

to install heating systems that run on renewable fuels, which are far

more expensive than gas-powered boilers.

The action was even more invasive than the European Union’s sprawling ban on gas-powered vehicles that was finalized just months before.

“[The EU] has taken an important step towards zero-emission mobility,” EU environment commissioner Frans Timmermans said on Twitter. “The direction is clear: in 2035 new cars and vans must have zero emissions.”

Wall Street’s $14 Trillion Exit

The Green policies emerging from Europe did little to alleviate

Americans’ concerns that the climate policies of central planners are

not driven by sound economics. Yet many similar policies have taken root

in the US.

As of March 2024, no fewer than nine US states

had passed laws to ban the sale of gas-powered cars by 2035. Meanwhile,

the Biden administration recently doubled down on an EPA policy to

begin a coerced phase-out of gas-powered vehicles — even though the federal effort to build out the charging stations to support EVs has flopped spectacularly (despite $7.5 billion in funding).

Despite federal subsidies for EVs, a majority of Americans remain unsold on them, and the sputtering EV market has left a wake of carnage. In June, the EV automaker Fisker Inc., which in 2011 received half a billion dollars in guaranteed loans from the US Department of Energy, filed for Chapter 11 bankruptcy in Delaware. (Fisker had long drawn comparisons to Solyndra, the solar panel company that went belly up in 2011 just two years after receiving $535 million from the US government.)

Fisker’s bankruptcy came just months after the New York Times reported on a massive exodus of capital from Climate Action 100+,

the world’s largest investor initiative on climate change. JPMorgan

Chase and State Street pulled all funds, while BlackRock, the world’s

largest asset manager, reduced its holdings and “scaled back its ties to

the group.”

“All told, the moves amount to a nearly $14 trillion exit from an

organization meant to marshal Wall Street’s clout to expand the climate

agenda,” the Times reported.

Days after the Times report, PIMCO also announced it was leaving Climate Action 100+. Invesco, which manages $1.6 trillion in assets, made its exit just two weeks later.

‘You Cannot Avoid the Consequences of Avoiding Reality’

There’s no doubt that the Green economy is in retreat, but the question is, Why?

First, it’s becoming apparent — especially in Europe where energy is

more scarce and expensive — that people are souring on Green policies.

As Teixera noted, voters don’t actually like being told what

car they must drive and how to cook their food and heat their homes. If

you own a swimming pool, you probably want to be able to heat it.

Policymakers talk about “quitting” fossil fuels, but in recent years

Europeans got to experience an actual fossil-fuel shortage following

Russia’s invasion of Ukraine, which disrupted fossil fuel imports. The

result was energy rationing, something Europeans don’t seem to care for.

This brings me to my second point. Green parties and

environmentalists have had success largely by getting people to focus on

the desired effect of their policies (saving people from climate

change) and to ignore the costs of their policies.

Politicians seem to grasp that their policies come with trade-offs,

which is why their bans and climate targets tend to be 10, 15, or 30

years into the future. This allows them to bask in the glow of their

climate altruism without dealing with the economic consequences of their

policies.

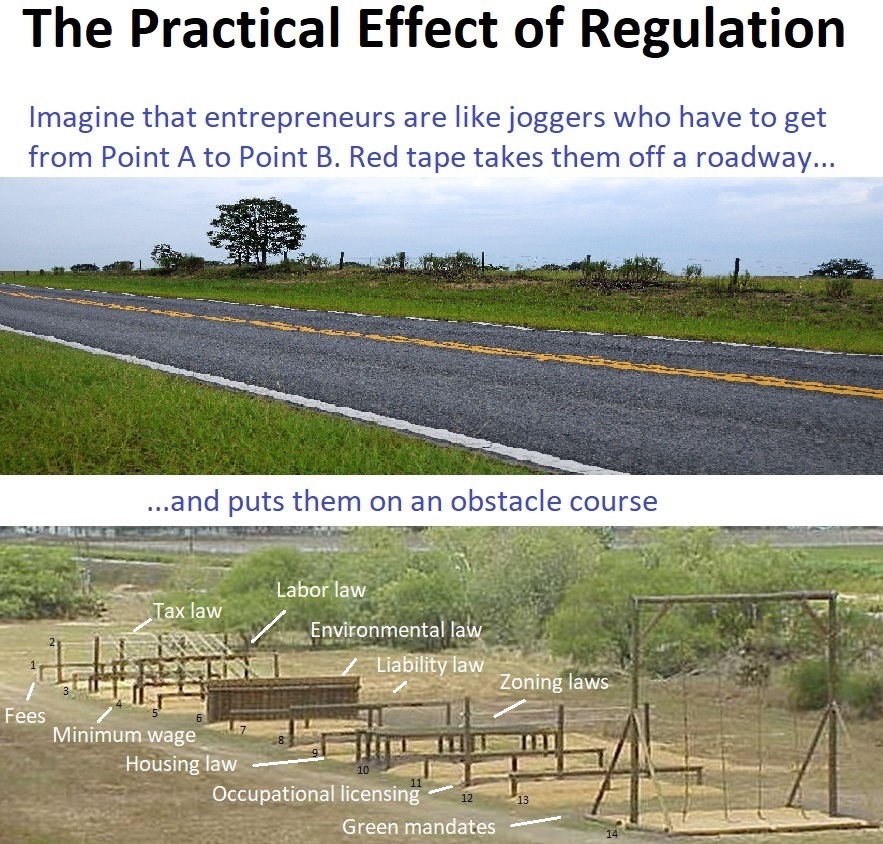

This is one of the most salient differences between economics and

politics. Economics is all about understanding the reality of

trade-offs, but politics is primarily about ignoring or concealing these

realities.

Few understood this better than the economist Henry Hazlitt, the author of Economics in One Lesson,

who wrote time and again about the tendency of politicians to overlook

the secondary consequences of their policies, which were responsible for

“nine-tenths of the economic fallacies that are working such dreadful

harm in the world today.”

For a time, politicians were able to ignore the secondary

consequences of their policies. But voters are finally getting a taste

of the costs of Green policies, and they don’t like it.

“You can avoid reality,” Ayn Rand once noted, “but you cannot avoid the consequences of avoiding reality.”

An ‘Iron’ Law

Fear of climate change has helped progressives and Greens gain more

economic control in recent decades, but even fear has its limits.

Teixera points to Roger Pielke, Jr., a University of Colorado Boulder professor who in 2009 wrote about the “iron law of climate policy.”

“Climate policy, they say, requires sacrifice, as economic growth and

environmental progress are necessarily incompatible with one another,”

he wrote. “This perspective has even been built into the scenarios of

the IPCC.”

Whether one accepts this premise — that economic growth and

environmental progress are necessarily incompatible — doesn’t matter.

What matters is that when economic growth policies collide with emission

reduction targets, economics wins.

It’s one thing to say that gas prices should be $9 a gallon, as physicist Steven Chu once did,

because climate change is a dire threat. It’s another thing to say this

while trying to become Energy Secretary, as Chu was while testifying

before the Senate in 2012:

Sen. Mike Lee: “So are you saying you no longer share the view that

we need to figure out how to boost gasoline prices in America?”

Chu: “I no longer share that view… Of course we don’t want the price of gasoline to go up; we want it to go down.”

You can call this the “iron law of climate policy,” or you can call

it common sense. (Who wants gas to go to $9 a gallon?) Essentially,

it’s lofty environmental goals colliding with economic and political

reality.

This phenomenon is also conspicuous in Joe Biden’s presidency. On day

one, the president nixed the Keystone XL Pipeline (for inexplicable

reasons), and would go on to declare global warming a greater existential threat than a nuclear war.

Yet he would later boast that his policies were lowering gasoline prices, and that he oversaw record-high US oil production.

This is the iron law of climate policy, and it explains why the Green economy is suddenly in retreat all over the world.

Not-So-‘Green’ Policies

The reality is that the Green agenda comes with steep trade-offs,

something Europeans, Americans, and Wall Street are finally beginning to

admit. But Europe’s energy policies haven’t just been unpopular; many of them haven’t even been “Green.”

For starters, electrical vehicles are hardly the environmental panacea

many claim them to be. In fact, EVs require much more energy to produce

on average than gas-powered vehicles, and also often run on electricity

generated by fossil fuels. This means that EVs come with their own

carbon footprints, and they tend to be much larger than most realize.

An analysis by the Wall Street Journal found that shifting all personal vehicles in the U.S to EVs would reduce global CO2 emissions by only 0.18 percent. This would do virtually nothing to change global CO2

emission trends, which data show are rising not because of European or

US personal vehicles, but from emerging economies like China.

And then there’s Germany’s bizarre decision to abandon nuclear power. Despite an eleventh-hour plea

from a group of scientists (including two Nobel laureates) who urged

lawmakers not to do so because it would exacerbate climate change,

Germany closed its last three nuclear power plants — Emsland in Lower

Saxony, Neckarwestheim 2 in Baden-Württemberg, and Isar 2 in Bavaria — in the middle of an energy crisis.

The move puzzled many around the world. After all, nuclear energy is

cleaner and safer than any other energy source with the exception of

solar, according to estimates from Our World in Data. Even more bizarre, Germany’s phaseout of nuclear power, which began in 2011, coincided with a return to coal.

Germany’s decision to ramp up coal production and shutter its last

nuclear plants is hardly consistent with the EU’s view that climate

change is a dire threat to human kind, many noted.

“No less a climate-change evangelist than Greta Thunberg has argued

publicly that, for the planet’s sake, Germany should prioritize the use

of its existing nuclear facilities over burning coal,” journalist

Markham Heid pointed out at Vox.

Meanwhile, in the US, where nuclear power has been steadily attacked

for decades by politicians and environmentalists, the Senate quietly passed (by a vote of 80–2!) a bill to support the deployment of nuclear facilities.

These anecdotes illustrate an important point: Green policies are not just unpopular and uneconomical; they are often senseless.

Few understand this better than Dutch farmers, who are being forced

to sell off their farms by politicians who have little understanding of

economics trade offs.

Jonathan Miltimore is the Managing

Editor of FEE.org and a Senior Writer at AIER. His writing/reporting has

been the subject of articles in TIME magazine, The Wall Street Journal,

CNN, Forbes, Fox News, and the Star Tribune.

Get notified of new articles from Jon Miltimore and AIER.

"

"