Back in 2012, I warned that the value-added tax (a hidden version of a national sales tax) was enabling bad fiscal policy in Japan, in large part because politicians wouldn’t make much-needed entitlement reforms if they had the option of raising the VAT.

Later that year, I repeated my warning, noting that politicians in Japan were becoming increasingly vocal about grabbing more money.

Unsurprisingly, these warnings had no effect. In 2013, Japan’s politicians announced the VAT would increase the following year.

Did the increase in the tax burden generate any subsequent good results?

Nope. The economy remained stagnant and debt continued to increase.

Needless to say, Japan’s politicians didn’t learn from this mistake. Notwithstanding my warnings in 2018 and 2019, they just increased the VAT yet again.

So how’s that working out for them?

In a column for the Wall Street Journal, Mike Bird discusses the economic impact of the most-recent increase in the value-added tax.

For what it’s worth, I don’t find this chart very persuasive.

Yes, consumption drops in the short run when there’s an increase in the VAT, but there doesn’t seem to be any impact on the long-run trend.

Moreover, I don’t think consumer spending is an important variable, at least not in the sense of driving the economy.

But I’m digressing. Let’s get back to Japan’s VAT mistake.

The Wall Street Journal opined on the issue earlier this week.

Especially not in Europe, where politicians have been increasing the VAT with disturbing regularity.

Needless to say, those VAT increases are having the same impact in Europe as they are in Japan – bigger government, more debt, and anemic economic performance.

Let’s close by citing three additional sentences from the WSJ editorial.

The fiscal pyromaniacs at the IMF want even further VAT increases in Japan.

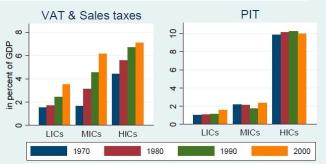

Indeed, this chart shows why the pro-tax crowd at the IMF is in love with the VAT. Simply stated, it’s a very effective money machine for bigger government.

Indeed, this chart shows why the pro-tax crowd at the IMF is in love with the VAT. Simply stated, it’s a very effective money machine for bigger government.

It enables politicians to siphon money from the productive sector of the economy, whether we’re looking at poor nations or rich nations.

By contrast, it’s difficult to generate more revenue from the personal income tax because of the Laffer Curve.

P.S. Some VAT advocates actually claim the levy is good for growth. That’s a nonsensical claim. VATs drive a wedge between pre-tax income and post-tax consumption. What they really mean to say is that VATs don’t do as much damage, on a per-dollar-raised basis, as conventional income taxes (with punitive rates and double taxation).

Later that year, I repeated my warning, noting that politicians in Japan were becoming increasingly vocal about grabbing more money.

Unsurprisingly, these warnings had no effect. In 2013, Japan’s politicians announced the VAT would increase the following year.

Did the increase in the tax burden generate any subsequent good results?

Nope. The economy remained stagnant and debt continued to increase.

Needless to say, Japan’s politicians didn’t learn from this mistake. Notwithstanding my warnings in 2018 and 2019, they just increased the VAT yet again.

So how’s that working out for them?

In a column for the Wall Street Journal, Mike Bird discusses the economic impact of the most-recent increase in the value-added tax.

Japan’s economy shrank sharply in the final three months of 2019, logging its second-worst quarter in the past decade. That would be easier to stomach if it weren’t because of a mistake policy makers have now made three times. In October, Japan raised its sales tax to 10% from 8%—and spending tanked. Household consumption fell 11.5% on an annualized basis in the October-December quarter, fueling a 6.3% fall in annualized gross domestic product. Sales-tax increases in 1997 and 2014 likewise knocked the economy off course. The three worst quarters for household consumption in the past quarter-century were those in which sales tax was raised. …the thinking that led to such destructive behavior is bizarrely resilient.Here’s the accompanying chart, which shows how every increase in the VAT caused a drop in consumption.

For what it’s worth, I don’t find this chart very persuasive.

Yes, consumption drops in the short run when there’s an increase in the VAT, but there doesn’t seem to be any impact on the long-run trend.

Moreover, I don’t think consumer spending is an important variable, at least not in the sense of driving the economy.

But I’m digressing. Let’s get back to Japan’s VAT mistake.

The Wall Street Journal opined on the issue earlier this week.

Unfortunately, other leaders aren’t learning the right lessons.The third time wasn’t the charm for Tokyo’s long-running attempt to increase its consumption tax. Data released Monday show Japan’s economy contracted in the last three months of 2019 as the tax hike hammered growth—as many warned and like the previous two times the tax has been raised since its 1989 introduction, in 1997 and 2014. …Wage growth is anemic despite a tight labor market, and the Labor Ministry calculates that inflation-adjusted pay fell 3.5% from 2012-2018. The tax rise creates a new and higher squeeze on household incomes. …The usual suspects are now calling for more Keynesian spending on public works and social spending. Three decades of similar blowouts have created the fiscal mess that always becomes justification for more consumption-tax hikes. …It’s too late for Japan to avoid the costs of Mr. Abe’s economic failures. But other governments can learn the lessons that Japan’s leaders refuse to heed.

Especially not in Europe, where politicians have been increasing the VAT with disturbing regularity.

Needless to say, those VAT increases are having the same impact in Europe as they are in Japan – bigger government, more debt, and anemic economic performance.

Let’s close by citing three additional sentences from the WSJ editorial.

The fiscal pyromaniacs at the IMF want even further VAT increases in Japan.

The International Monetary Fund thinks the consumption-tax rate will have to rise to 15% over the next decade, and to 20% by 2050. But first the fund’s wizards say Tokyo must expand its Keynesian spending to make the economy “strong” enough to bear the tax hikes to pay for the spending. Got that?I wrote last year about the IMF’s perverse fixation on ever-increasing VAT burdens in Japan, so I’m not surprised that the international bureaucracy is continuing its campaign.

Indeed, this chart shows why the pro-tax crowd at the IMF is in love with the VAT. Simply stated, it’s a very effective money machine for bigger government.

Indeed, this chart shows why the pro-tax crowd at the IMF is in love with the VAT. Simply stated, it’s a very effective money machine for bigger government.It enables politicians to siphon money from the productive sector of the economy, whether we’re looking at poor nations or rich nations.

By contrast, it’s difficult to generate more revenue from the personal income tax because of the Laffer Curve.

P.S. Some VAT advocates actually claim the levy is good for growth. That’s a nonsensical claim. VATs drive a wedge between pre-tax income and post-tax consumption. What they really mean to say is that VATs don’t do as much damage, on a per-dollar-raised basis, as conventional income taxes (with punitive rates and double taxation).

No comments:

Post a Comment