Flu season is ramping up and the cases that have already occurred are being used to make predictions on what will be coming down the pike when it peaks in a month or two.

So far this flu season, influenza A (H3N2) viruses have been predominant in the United States (represented by the red bars in the graph below.) This information interests health officials as this particular strain is more concerning than others. Previous flu seasons when H3N2 led the pack were more severe, especially among young children and older adults. Between the years 2003 to 2013, the three flu seasons that were dominated by H3N2 strains of the flu had the highest mortality rates.

Flu season is ramping up and the cases that have already occurred are being used to make predictions on what will be coming down the pike when it peaks in a month or two.

So far this flu season, influenza A (H3N2) viruses have been predominant in the United States (represented by the red bars in the graph below.) This information interests health officials as this particular strain is more concerning than others. Previous flu seasons when H3N2 led the pack were more severe, especially among young children and older adults. Between the years 2003 to 2013, the three flu seasons that were dominated by H3N2 strains of the flu had the highest mortality rates.

What does the name H3N2 mean? There are many different flu strains and one place that they differ is in two major proteins on the outside of the virus - the Hemagglutinin (H) and Neuraminidase (N). For more on this, please read here.

This news is most concerning to those affected by H3N2 which, according to the graph below, has been older people (shown in light purple.) The numbers of positive tests for H3N2 are shown on the fourth bar down and show that the group with the largest number of cases are in people greater than 64 years old (over 35%.)

What should we expect in the next few months, then? Looking at the trends from the past few years, there is reason to be concerned. The graph below shows the number of visits for influenza-like illness (not confirmed cases) for the last few years. The bold, red line below shows the numbers for the current season - riding along the path of the early spiking 2014-2015 season. Only time will tell where the number of cases will take us from here, but, we're off to a very foreboding start.

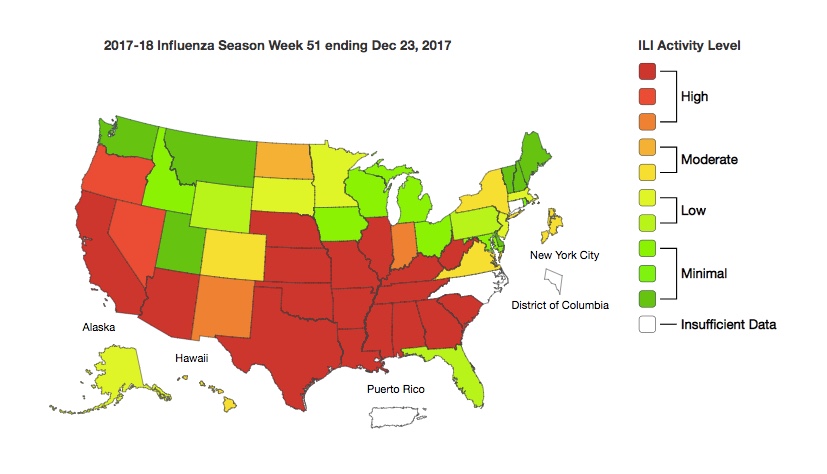

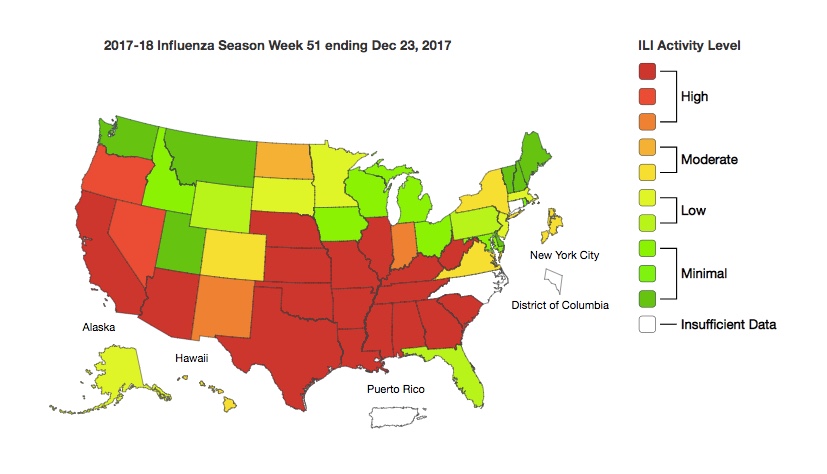

Other data shows that the southern region of the United States is reporting more flu-like activity so far. This may be because they are seeing more of it, but, it also could be simply that they are reporting more of it.

Lastly, there are the heartbreaking stories emerging on social media of children who are dying from the flu. The CDC reports that the majority of children who die from the flu are not vaccinated. Even though the vaccine is not perfect, and is not a guarantee against all flu-like illnesses, what is known is that it will offer protection and it will lessen the course of the disease, even if you or your child contract influenza. And, it is not too late! It takes about two weeks for your body to build up immunity the virus after vaccination. Being protected come mid-January is important as that is when cases tend to increase. We will keep the updates coming here at ACSH, but, in the meantime, please take another look at these graphs, realize that this looks like its going to be a rough flu season, and protect yourself and your children.

H1N1? H2N5? What Do Flu Names Mean?

So far this flu season, influenza A (H3N2) viruses have been predominant in the United States (represented by the red bars in the graph below.) This information interests health officials as this particular strain is more concerning than others. Previous flu seasons when H3N2 led the pack were more severe, especially among young children and older adults. Between the years 2003 to 2013, the three flu seasons that were dominated by H3N2 strains of the flu had the highest mortality rates.

What does the name H3N2 mean? There are many different flu strains and one place that they differ is in two major proteins on the outside of the virus - the Hemagglutinin (H) and Neuraminidase (N). For more on this, please read here.

This news is most concerning to those affected by H3N2 which, according to the graph below, has been older people (shown in light purple.) The numbers of positive tests for H3N2 are shown on the fourth bar down and show that the group with the largest number of cases are in people greater than 64 years old (over 35%.)

What should we expect in the next few months, then? Looking at the trends from the past few years, there is reason to be concerned. The graph below shows the number of visits for influenza-like illness (not confirmed cases) for the last few years. The bold, red line below shows the numbers for the current season - riding along the path of the early spiking 2014-2015 season. Only time will tell where the number of cases will take us from here, but, we're off to a very foreboding start.

Other data shows that the southern region of the United States is reporting more flu-like activity so far. This may be because they are seeing more of it, but, it also could be simply that they are reporting more of it.

Lastly, there are the heartbreaking stories emerging on social media of children who are dying from the flu. The CDC reports that the majority of children who die from the flu are not vaccinated. Even though the vaccine is not perfect, and is not a guarantee against all flu-like illnesses, what is known is that it will offer protection and it will lessen the course of the disease, even if you or your child contract influenza. And, it is not too late! It takes about two weeks for your body to build up immunity the virus after vaccination. Being protected come mid-January is important as that is when cases tend to increase. We will keep the updates coming here at ACSH, but, in the meantime, please take another look at these graphs, realize that this looks like its going to be a rough flu season, and protect yourself and your children.

H1N1? H2N5? What Do Flu Names Mean?

By Julianna LeMieux — October 4, 2016 @ American Council on Science and Health

The fall brings with it cooler days, apple picking and flu season.

|

| Influenza virus |

We know what the symptoms of the flu are, how it is spread and the importance of getting a flu shot. What we may not know is the difference between the strains of the influenza virus and why are they referred to by the letters H and N - followed by numbers.

This may be a bit "inside biology" for some, but, in case you are wondering what these names mean and how they come about, here is a look into the virology behind the influenza virus.

Strains of influenza are characterized by two proteins that are on the outer surface of the virus: hemagglutinin and neuraminidase. This is where the "H" and "N" in the name come from. The proteins can be seen in the picture above, represented by the blue "spikes" on the outside of the virus. Both of these proteins are required for the virus to cause an infection and perform complementary functions. The hemagglutinin is critical for the virus to be able to attach to, and then enter the cell. Without hemagglutinin, the entire process of infection could not be initiated.

Once in the cell, the virus takes over the normal cell machinery and uses it to make many copies of itself.

Then, the neuraminidase enzyme comes into play. Neuraminidase is required for the newly made viruses to escape the host cell, where they can then perpetuate the infection. It's role is to clip the newly made viruses from the membrane of host cell and release them. Without neuraminidase, the new viruses would stay attached to the host cell, unable to infect new cells.

When a person becomes infected with influenza virus, their body's immune system responds by making antibodies to the H and N proteins. Then the antibodies bind to the H and N proteins, and block them from doing their job, stopping the virus in its tracks.

However, with influenza virus, the situation is even more complicated.

Influenza's complexity starts with the fact that there are 14 versions of H protein and 9 versions of N which means that there are a total of 144 varieties of flu. Not all of these 144 are infective.

Additionally, there are two major processes that create a complicated situation even worse. These are called antigenic drift and antigenic shift.

Antigenic drift means that either H or N change in a particular strain. This results in new strains, and this trips up the immune system. When H and N mutate, it is possible that they change so much that the antibodies may not bind to them anymore, leaving the virus fully infective.

The concept of antigenic shift is more complicated, but, stay with me for a moment. In order to understand antigenic shift, first we must understand how the genome of influenza is stored inside the virus. Influenza belongs to the orthomyxoviridae family of viruses. This means that, unlike our genes, which are made up of DNA, the flu virus's genome is made up of RNA - eight separate pieces of RNA. Flu is an example of an RNA virus with the hemagglutinin and neuraminidase genes are found on different pieces of RNA.

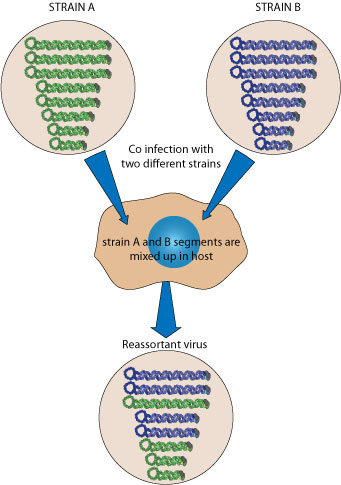

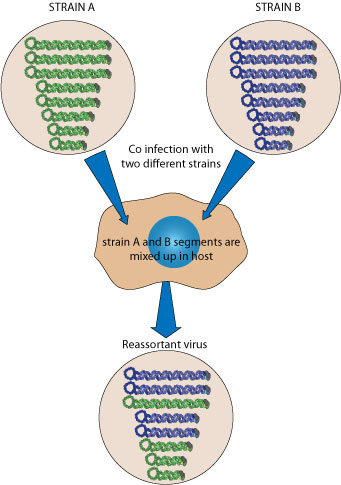

When two different strains of flu infect a cell at the same time, the pieces of RNA (eight from each virus) mix together. This is called reassortment and results in a new strain.

In looking at the figure below, let's say that strain A (with the green RNA) is an H1N1 virus and strain B (with the blue RNA) is an H2N5. In the figure, both of these viruses are infecting the same cell at the same time. When in the cell, the 16 pieces of RNA mix together and the virus that is released from the cell is different (a combination of some green RNA and some blue RNA) from either of the original ones that went in.

This process makes pandemics more likely because the strain that results from the reassortment may be a more dangerous strain and also one that no one has been exposed to before.

Within the past century, there have been four flu pandemics (worldwide epidemics.) They occurred in 1918 (H1N1 - swine flu), 1957 (H2N2), 1968 (H3N2) and 2009 (H1N1) and experts agree that it is not a matter of if, but when, the next pandemic will strike. It is not simple to predict which flu strain will be wreaking havoc next and the flu vaccine varies in how effective it is from year to year.

Knowing about the complexity of the influenza virus's genome and its ability to undergo antigenic shift and drift help us understand, at least to some extent, what we are up against each year.

This may be a bit "inside biology" for some, but, in case you are wondering what these names mean and how they come about, here is a look into the virology behind the influenza virus.

Strains of influenza are characterized by two proteins that are on the outer surface of the virus: hemagglutinin and neuraminidase. This is where the "H" and "N" in the name come from. The proteins can be seen in the picture above, represented by the blue "spikes" on the outside of the virus. Both of these proteins are required for the virus to cause an infection and perform complementary functions. The hemagglutinin is critical for the virus to be able to attach to, and then enter the cell. Without hemagglutinin, the entire process of infection could not be initiated.

Once in the cell, the virus takes over the normal cell machinery and uses it to make many copies of itself.

Then, the neuraminidase enzyme comes into play. Neuraminidase is required for the newly made viruses to escape the host cell, where they can then perpetuate the infection. It's role is to clip the newly made viruses from the membrane of host cell and release them. Without neuraminidase, the new viruses would stay attached to the host cell, unable to infect new cells.

When a person becomes infected with influenza virus, their body's immune system responds by making antibodies to the H and N proteins. Then the antibodies bind to the H and N proteins, and block them from doing their job, stopping the virus in its tracks.

However, with influenza virus, the situation is even more complicated.

Influenza's complexity starts with the fact that there are 14 versions of H protein and 9 versions of N which means that there are a total of 144 varieties of flu. Not all of these 144 are infective.

Additionally, there are two major processes that create a complicated situation even worse. These are called antigenic drift and antigenic shift.

Antigenic drift means that either H or N change in a particular strain. This results in new strains, and this trips up the immune system. When H and N mutate, it is possible that they change so much that the antibodies may not bind to them anymore, leaving the virus fully infective.

The concept of antigenic shift is more complicated, but, stay with me for a moment. In order to understand antigenic shift, first we must understand how the genome of influenza is stored inside the virus. Influenza belongs to the orthomyxoviridae family of viruses. This means that, unlike our genes, which are made up of DNA, the flu virus's genome is made up of RNA - eight separate pieces of RNA. Flu is an example of an RNA virus with the hemagglutinin and neuraminidase genes are found on different pieces of RNA.

When two different strains of flu infect a cell at the same time, the pieces of RNA (eight from each virus) mix together. This is called reassortment and results in a new strain.

In looking at the figure below, let's say that strain A (with the green RNA) is an H1N1 virus and strain B (with the blue RNA) is an H2N5. In the figure, both of these viruses are infecting the same cell at the same time. When in the cell, the 16 pieces of RNA mix together and the virus that is released from the cell is different (a combination of some green RNA and some blue RNA) from either of the original ones that went in.

This process makes pandemics more likely because the strain that results from the reassortment may be a more dangerous strain and also one that no one has been exposed to before.

Within the past century, there have been four flu pandemics (worldwide epidemics.) They occurred in 1918 (H1N1 - swine flu), 1957 (H2N2), 1968 (H3N2) and 2009 (H1N1) and experts agree that it is not a matter of if, but when, the next pandemic will strike. It is not simple to predict which flu strain will be wreaking havoc next and the flu vaccine varies in how effective it is from year to year.

Knowing about the complexity of the influenza virus's genome and its ability to undergo antigenic shift and drift help us understand, at least to some extent, what we are up against each year.

No comments:

Post a Comment