Christopher Lingle September 1, 2021 @ American Institute for Economic Research

Christopher Lingle September 1, 2021 @ American Institute for Economic Research

Science, as opposed to pseudoscience, scientific denialism or conspiracy theories, involves a willingness to inspect data and be open about as well as to view hypotheses and the evidence offered to support them with skepticism. Since empirical evidence can be manipulated or even used to disguise ideology or wishful thinking in support of a particular hypothesis, it is misleading, even dishonest, to insist that an objective, immutable “consensus” exists.

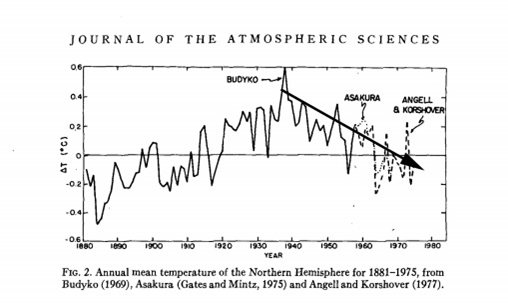

While there are certain “facts” that are widely accepted, e.g., that there is a global warming trend, the nature of the trend is contested and there is considerable dispute as to what the cause of the change or warming might be. But then, not so long ago, there was a scientific consensus that there was a long-term cooling trend for the land areas of North America. (see figure below).

Clearly, claims of a scientific consensus relating to anthropogenic global warming are not without controversy. In a world familiar with “cancel culture,” it would not be surprising that a dominant view could be contrived by punishing, marginalizing, or excluding dissenting views.

For its part, the scientific method generally involves the following sequence: observe, hypothesize, predict, test, analyze, and revise. But experimental confirmation cannot establish “truth” in any theory since future testing can render a theory to be untenable. While predictability is compelling by providing believability based on data, neither science nor any empirical theory reveals what is true, per se.

Indeed, the goal of science is to seek failure, not truth. As it is, “scientists” can engage in misinformation, including “cherry-picking” data, sloppy data collection or analysis, unintended errors, fraud (e.g., false or fabricated data) or “good intentions” based on cognitive or confirmation bias.

As such, all theories are tentative and subject to revision if more or better or contrary evidence appears. Being a skeptic is the mark of someone ready to reject ideas they believe lack sufficient evidence and to accept new ideas based on reliable evidence and reproducible results.

Rather than applaud conventional scientific wisdom said to support a consensus, we should celebrate uncertainty, honesty and openness that underpin science. Indeed, humility and self-criticism of one’s own work is as important as are communal and institutional critiques.

Unfortunately, belief in the “truth” relating to global warming (sic., climate change) has induced suggestions for skeptics to be forcibly silenced, even prosecuted for crimes. Meanwhile, insistence on the existence of a “scientific consensus” concerning the nature and causes of alterations is likely to direct funding and acceptance of research proposals towards those that promote the dominant view.

To that end, 19 federal agencies received climate change funding of more than $13 billion in 2017. The total spending on climate studies between 1989 and 2009 exceeded $32 billion, not including $79 billion spent for climate change technology research, foreign aid and tax breaks for “green energy.” As such, the losses of sinecures and access to largesse would be massive if global warming or climate change were discovered to be less than an existential problem.

It turns out that there is so much complexity about the various influences on climate that it is much more difficult than normally assumed. For example, the sun does not provide a constant intensity nor does the Earth rotate around it in a constant orbit, so that solar flaring and the wobbling of the Earth about its axis contribute to variations in solar heating.

There is also enormous complexity of the climatic impacts of ocean currents and regular climate events (e.g., El Niño and La Niña), making it difficult to determine whether average global sea surface temperatures are rising or falling. Indeed, oceanic convection at great depths and present in a few locations in the world is thought to connect the properties of the surface ocean and deep ocean, thus influencing the global thermohaline circulation and climate.

While the deep convective process is seasonally intermittent and relatively compact, observations and quantifying the transfer of deep water involve a difficult sampling problem. Variations in interannual surface salinity influence the rate of oceanic convection and poleward heat transport (thermohaline circulation). But insufficient accuracy in the measurements of these variations on a global basis make it difficult to provide reliable long-time-scale climate prediction and modeling.

Since hurricanes require warm sea surface temperatures (SSTs), the rise in tropical Atlantic sea surface temperatures above normal are inevitably interpreted to be evidence of global warming. But the year after Hurricane Katrina’s landfall, the Atlantic hurricane season was remarkably mild with only 3 named tropical storms compared to 9 at the same point the previous year when at least one hurricane normally should have appeared.

It seems that large areas in the tropical Atlantic were a bit cooler than normal, leading to a 12-year hurricane drought, the longest in US history, ending in 2017. On average, the upper ocean cooled dramatically between 2003 and 2005, a change that reversed 20% of the warming that supposedly had occurred over the previous 48 years.

Interestingly, hurricane droughts are also coincidental with land-based droughts. While coastal areas are deprived of the rainfall that accompanies the landfall of tropical storms and hurricanes to replenish groundwater, nearby inland regions also suffer from arid spells.

Yet climate activists tend to insist that both were due to rising average global temperatures. But global warming will cause some areas to be drier and less hospitable for food production while other areas will be wetter and more hospitable for agriculture. In all events, the net impact remains uncertain.

While the complexity of climate makes it difficult to make accurate models of the inherent stability of the overall system, there are stabilizing feedback mechanisms that keep the climate system from spinning out of control. These stabilizing forces in the climate system ensure that global temperatures do not have excessive variation.

For example, clouds and water vapor have dominant roles in determining average global temperatures. But there is no clear idea about the response of clouds to a warming tendency from slow increases in carbon dioxide content of the atmosphere. Nor is there a clear understanding of the response of precipitation systems to warming.

Precipitation results when the atmosphere is saturated with water vapor from surface evaporation, and water vapor causes at least 90% of the Earth’s greenhouse effect. As such, an increase in hurricane intensity could be natural and part of an efficient element of the climate system that removes both atmospheric water vapor and excess heat from the ocean.

Scientific arguments about climate change seem to be the centerpiece of the coming “climate action” policies that are being touted as part of the “Great Reset” that foresees the need for a major alteration in the global economy. The restrictions on human liberty and private property imposed by governments in response to the Covid-19 pandemic are likely to be only an “appetizer” for an expansion of political control to address climate change.

For context, consider that the UN Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change (IPCC) issued its sixth report since 1990, announcing a “Code red for humanity” based on many factors, including an “irreversible” rise in sea level. The report insists that reductions in emissions of carbon dioxide and other greenhouse gasses (GHGs) are necessary to improve air quality and retard the rise of average global temperatures.

While evidence can be found for the certainty of rising sea levels, alternative interpretations of the same data source suggest the effect may be minimal (i.e., 3 inches over 100 years) such that there might be enough time to adjust. But as seen in the IPCC report, discussions of environmental issues tend to use an alarmist tone rather than relying on a neutral, purely informational approach. Indeed, neutral reports tend to be considered overly optimistic.

When science is mixed with politics, the result tends to be politics in its purest and most restrictive form. After all, political agents can be expected to look to “science” to provide a cover for expanded interventions or claims on resources that were previously considered to be unacceptable.

No comments:

Post a Comment