The 1918 Spanish flu was a killer of historic proportions.

Michael J. Totten Autumn 2020 @ City Journal, published with permission. I recommend subscribing, and it's free.

No one knows for sure where it started. There was no ground zero, no “Wuhan.” It may have begun in Europe or in East Asia, but the first confirmed cases appeared in rural Haskell County, Kansas, with the first large and verified outbreak erupting at an army base there. Soldiers traveling to World War I battlefields then spread it to Europe; and from there, it encircled the globe.

The H1N1 virus of 1918 was roughly 25 times more lethal than the seasonal flu and also more deadly than the novel SARS-CoV-2 coronavirus that causes Covid-19, especially as the latter’s mortality rate is declining now that we’re better able to treat it. It killed an estimated 2.5 percent of its victims. Life expectancy in the United States plunged by more than ten years. This was partly due to the flu itself—at its peak, it killed more people than everything else combined—and partly because it knocked hospitals out of commission almost everywhere, preventing doctors and nurses from treating much else.

“They called the plague of 1918 influenza,” Gina Kolata writes in her book Flu: The Story of the Great Influenza Pandemic of 1918 and the Search for the Virus That Caused It, “but it was like no influenza ever seen before. It was more like a biblical prophecy come true, something from Revelations that predicted that first the world was to be struck by war, then famine, and then, with the breaking of the fourth seal of the scroll foretelling the future, the appearance of a horse, ‘deathly pale, and its rider was called Plague, and Hades followed at its heels.’ ”

Coronaviruses emerge from bats, flu viruses from birds. Bats and birds have adapted to these viruses so perfectly that they don’t even get sick when they carry them. The overwhelming majority of the millions of viruses that infect animals around the world have no effect on humans. Before a zoonotic virus can infect a person, it must transform itself either through mutation or, more likely, through genetic recombination that becomes possible when it first jumps to an intermediate species. Middle East respiratory syndrome (MERS), for instance, is caused by a bat coronavirus that can leap to humans after infecting a camel. (It kills 20 percent of its victims; thankfully, it isn’t very contagious.) Novel flu viruses often leap from birds to pigs, whose immune systems closely resemble our own. If a flu virus manages to modify itself well enough to survive in a pig, or if it combines itself inside a pig’s body with an endemic flu virus that can already infect humans, a brand-new virus, to which no one on earth has immunity, can emerge. It has happened repeatedly; it happened in 1918, and it is sure to happen again.

The novel coronavirus that causes Covid-19 is a big bomb with a long fuse. It can take two weeks for a person to test positive for it after exposure and then several more weeks or even another month or longer to die from it. The 1918 flu virus was different. “The strongest, the healthiest, the most robust people in the county,” John Barry writes in The Great Influenza, “were being struck down as suddenly as if they had been shot.” That sounds strange, even impossible. It takes time for any disease to establish a foothold and spread throughout the body after initial exposure. But viruses don’t multiply in the body in a linear fashion—especially not the 1918 virus. Each virus that invaded and hijacked a human cell made hundreds of thousands of copies of itself inside that cell over a ten-hour period. Then each of those hundreds of thousands of viruses burst forth at the same time and went on to hijack more cells and make millions more copies. So every ten hours, the flu became hundreds of thousands of times stronger. The number of viruses produced after several ten-hour generations can stagger the minds even of mathematical geniuses. (How many viruses is five hundred thousand times five hundred thousand?)

So yes, people literally collapsed while walking down the street, as if shot. Some died within hours. Victims were so starved of oxygen that their faces and bodies turned black-and-blue. Blood poured from their noses, mouths, eyes, and even their ears. Lungs were so ravaged that doctors had seen such destruction only in the victims of poison gas attacks in the trenches of Europe and those killed by the pneumonic plague, the respiratory version of the Black Death.

“Although about 20 percent of its victims had a mild disease and recovered without incident,” Kolata writes, “the rest had one of two terrifying illnesses. Some almost immediately became deathly ill, unable to get enough oxygen because their lungs had filled with fluid. They died in days, or even hours, delirious with a high fever, gasping for breath, lapsing at last into unconsciousness. In others, the illness began as an ordinary flu, with chills, fever, and muscle aches, but no untoward symptoms. By the fourth or fifth day of the illness, however, bacteria would swarm into their injured lungs and they would develop pneumonia that would either kill them or lead to a long period of convalescence.” Barry writes of how people were “terrified that, no matter how mild the symptoms seemed at first, within them moved an alien force, a seething, spreading infection, a live thing with a will that was taking over their bodies.”

The staggering 100 million death toll was bad enough, but it came with an especially cruel twist: the disease was especially lethal to young people. Those in their prime, in their twenties and thirties, were by far the most likely to die. And among that group, pregnant women were even more vulnerable. As many as 10 percent of young adults worldwide were cut down. Hospitals strangely reported few extreme cases in elderly people, with the vast majority of those who died younger than 40. Various theories attempt to explain why. The most convincing is that many young adults suffered a “cytokine storm,” the immune system’s hydrogen bomb—a dramatic overreaction to an otherwise moderate infection that kills healthy cells along with the pathogen that it has been unleashed to destroy. Elderly people in 1918 rarely suffered such a cytokine storm. Their aging immune systems weren’t strong enough to mount one. And children often fare better with diseases than adults, anyway, from the so-called childhood diseases like measles and chicken pox to Covid-19. But young adults in 1918 were felled as if that were the pandemic’s purpose.

Flu viruses mutate constantly, especially the antigen, the part of a pathogen that the immune system recognizes and binds to when it fights back. A viral antigen functions almost like a flag or a military uniform identifying it as a known enemy. When the antigen mutates, the immune system no longer recognizes the invader, so it fails to wage an effective defense before the disease can establish a foothold. Flu antigens are unstable and constantly changing, which is why we need a new vaccine every year that includes antigens of the viruses currently circulating.

There’s a difference, though, between “antigenic drift” and “antigenic shift.” If a flu virus antigen mutates a little bit, the immune system can still mount an effective, if belated, defense, reducing the severity of the disease. Antigenic shift is worse—the stuff of an epidemiologist’s nightmares. That’s when the antigen changes so completely that nobody can recognize it, leaving the entire human race exposed and defenseless. This is what makes novel pandemic viruses so much more dangerous than endemic seasonal viruses. With a novel pandemic virus, no herd immunity exists, and the virus can wash over the entire human race like a tsunami.

But there was still some immune-system resistance in some parts of the world to the 1918 virus, mostly among Europeans, Asians, and their descendants, whose ancestors had survived repeated flu pandemics in decades and centuries past. “Survivors of plagues,” Kolata writes, “were the genetically lucky ones who had inherited a resistance to the disease-causing organisms. Even in the most extreme plagues, there are resistant people who either do not become infected, no matter how many times they are exposed to the sickness, or who get only a mild disease and recover. When everyone else is dying, the resistant people will be the ones who remain to propagate. Their genes will begin to predominate. And those who were genetically susceptible to the devastating illnesses would lose out in the great Darwinian struggle.”

People in Africa, the South Pacific, and the Arctic were more vulnerable. And they died in much larger numbers. So while the flu killed “only” 1 percent or 2 percent of its victims in the Western world, 3 percent to 6 percent of Africa’s population died in a few weeks. Some villages were annihilated down to the last child. In Fiji, 14 percent of the entire population was killed in just 16 days. “It was as if the virus were a hunter,” Barry writes. “It was hunting mankind. It found man in the cities easily, but it was not satisfied. It followed him into towns, then villages, then individual homes. It searched for him in the most distant corners of the earth. It hunted him in the forests, tracked him into jungles, pursued him onto the ice. And in those most distant corners of the earth, in those places so inhospitable that they barely allowed man to live, in those places where man was almost wholly innocent of civilization, man was not safer from the virus. He was more vulnerable.”

The virus killed up to one-third of the entire population of Canada’s northern Labrador region. In some Alaska villages, as many as 90 percent of adults perished. Up there especially, it looked and felt like the end of the world. Victor Vaughan at the Council of National Defense wrote that “if the epidemic continues its mathematical rate of acceleration, civilization could easily disappear . . . from the face of the earth within a matter of a few more weeks.”

The pandemic came in three distinct waves. The first, which began in Kansas, was the equivalent of a bad seasonal flu in a normal year. Then it quieted down during the summer, as seasonal flus always do, but it returned in a second wave during the fall, and the second wave was apocalyptic. When it had smoldered largely undetected during the summer, the virus had mutated into a perfect killing machine.

It exploded with the suddenness of a meteor strike and infected staggering numbers of people in a wide area more or less simultaneously. Barry likens it to the process of a pot of water coming to a boil. “First an isolated bubble releases from the bottom and rises to the surface,” he writes. “Then another. Then two or three simultaneously. Then half a dozen. But unless the heat is turned down, soon enough all the water within the pot is in motion, the surface a roiling violent chaos.”

It hit Philadelphia particularly hard. Local officials wouldn’t even consider imposing social distancing recommendations. Ignoring warnings by local doctors, they refused to cancel an upcoming Liberty Loan parade, even after a nearby military base experienced a surge of infections. So tens of thousands of people who had no idea that they were in danger gathered in one place, jam-packed together for hours. Some of them—soldiers from the base, probably—were infected and didn’t know it.

They spread the disease during their brief pre-symptomatic period, and the pandemic established a foothold in the city. It didn’t relent until it ran out of victims. Three days after the parade, every bed in the city’s hospitals was full. Hundreds of people died daily. Local officials finally closed businesses and schools; but by then, it was too late. Hundreds of thousands were already sick, and they had all fallen ill at the same time. The flu killed 11,000 people in Philadelphia in a single month.

The health-care system collapsed: not only were the hospitals out of beds; there were no tables in morgues and no coffins for the cemeteries. “Corpses,” Barry writes, “had backed up in homes. They lay on porches, in closets, in corners of the floor, on beds. Children would sneak away from adults to stare at them, to touch them; a wife would lie next to a dead husband, unwilling to move him or leave him. The corpses, reminders of death and bringers of terror or grief, lay under ice at Indian-summer temperatures. Their presence was constant, a horror demoralizing the city.” Then the city, he writes, “began to implode in chaos and fear.” Priests drove wagons down residential streets and told the living to bring out their dead. And what happened in Philadelphia was soon happening everywhere, not just in America but around the world.

The pandemic exploded amid World War I, after President Woodrow Wilson had already imposed a Fidel Castro–style censorship regime that suppressed criticism of the government or any other writing or speech that might hurt wartime morale. Wilson’s Sedition Act of 1918 criminalized “disloyal, profane, scurrilous, or abusive language” and punished offenders with up to 20 years in prison. Newspapers and magazines considered “unpatriotic” were canceled, as we would say today. Dissenting civilians were intimidated, and sometimes worse. The government spied on private citizens and arrested them even for casual offhand remarks. These efforts were bolstered by the American Protective League, a secret police network staffed by 250,000 employees who spied on citizens in 600 cities and towns. They implanted themselves as undercover agents in places like factories, where they could listen to conversations. They inspired schoolboys to form their own informant organization, the Anti–Yellow Dog League.

“Everywhere,” Barry writes, the APL “spied on neighbors, investigated ‘slackers’ and ‘food hoarders,’ demanded to know why people didn’t buy—or didn’t buy more—Liberty Bonds.” Government posters and ads encouraged friends and neighbors to turn in their own friends and neighbors. Wilson was a Democrat and a leading light of the progressive movement, but not even his political opposition in the Republican Party complained about any of this. Republicans backed the White House’s police state wholeheartedly.

Newspapers, either terrified of or in league with the White House, lied about the pandemic daily, even as it scythed through the American population. It’s just the flu, the papers said; calm down. Conspiracy theorists accused the Germans of creating the virus in a lab. The same thing happened in Europe. “Further from the theatre of war,” Spinney writes, “people followed the time-honoured rules of epidemic nomenclature and blamed the obvious other. In Senegal it was the Brazilian flu and in Brazil the German flu, while the Danes thought it ‘came from the south.’ The Poles called it the Bolshevik disease, the Persians blamed the British.”

Most European countries likewise imposed wartime censorship regimes no less extreme than Wilson’s. Spain was an exception. A neutral in the war, Spain still had a free press. Spanish journalists were still more or less free to write whatever they wanted. “When the flu arrived in Spain in May,” Spinney writes, “most Spanish people, like most people in general, assumed that it had come from beyond their own borders. In their case, they were right. It had been in America for two months already, and France for a matter of weeks at least. Spaniards didn’t know that, however, because news of the flu was censored in the warring nations.”

So when free Spanish journalists published newspaper articles about a terrifying wave of influenza, it appeared that Spain was the only country on earth suffering from this strange new disease. That’s how what could have been called the Kansas flu became the Spanish flu.

Thanks to Wilson and his censorship regime, American citizens, including government officials, were living deep inside an informational black hole when the pandemic struck. The government did not fill the void. There was no pandemic task force, no press conferences, no trusted medical experts informing the public via newspaper or radio interviews. There was no plan. There was nothing.

Wilson never spoke about the disease publicly. According to Barry, there is no evidence that he even spoke about it privately or asked a single person what might be done about it. He utterly ignored it and abandoned the country, even as the death toll exceeded the number of dead from every war in American history combined. American public health officials hardly did anything to stop the spread in 1918. Some cities closed businesses like movie theaters for a few days, but that was about it. Many cities didn’t even do that much.

The pandemic killed 675,000 Americans, the population-adjusted equivalent of roughly 2 million Americans today, but Rupert Blue, Wilson’s man at the Public Health Service, actively sabotaged research into the disease by refusing to fund it. Some governors begged for assistance, but little help arrived, and most local governments abdicated responsibility, just as the federal government did. Most of them, too, behaved as though the pandemic didn’t exist, including Thomas B. Smith, mayor of Philadelphia, America’s hardest-hit city. Like Wilson, he never mentioned it once.

Journalists failed as spectacularly as the government. “As terrifying as the disease was,” Barry writes, “the press made it more so. They terrified by making little of it, for what officials and the press said bore no relationship to what people saw and touched and smelled and endured. People could not trust what they read. Uncertainty follows distrust, fear follows uncertainty, and, under conditions such as these, terror follows fear.” Officials and journalists who did bother to say anything insisted that the terror sweeping the country was more dangerous than the flu. The more they lied, the more terrified people became.

San Francisco was an exception. It fared better during the brutal second wave than any other major American city—partly, Barry thinks, because of its experience with a historic and devastating earthquake 12 years earlier. The city had already gone through a large-scale disaster that required mass mobilization and the building of a more robust public-health network. Local officials were frank about the threat, and they closed businesses and urged everyone to wear masks. “In San Francisco,” Barry writes, “people felt a sense of control.”

The failures in managing the illness were not uniquely American—they were civilization-wide. “The major Italian newspaper the Corriere della Sera took an original stance in reporting daily death tolls from flu,” Spinney writes, “until civil authorities forced it to stop doing so on the grounds that it was stirring up anxiety among the citizenry. . . . The authorities don’t seem to have realised that the paper’s ensuing silence on the matter bred even greater anxiety.”

As Barry wrote in 2004: “Those in authority must retain the public’s trust. The way to do that is to distort nothing, to put the best face on nothing, to try to manipulate no one. Lincoln said that first, and best. A leader must make whatever horror exists concrete. Only then will people be able to break it apart.”

The Spanish flu pandemic lasted a year and a half, with different parts of the world hardest hit at different times. The virus couldn’t last a year and a half everywhere: it was so ferociously infectious that it exploded throughout a given population until a critical mass of people were either dead or immune. When it ran out of victims in one place, it moved on to pulverize somewhere else.

The third and final wave wasn’t as virulent as the second. The virus had mutated into a somewhat less lethal form, though it was still vicious—if the third wave were treated as its own isolated outbreak, it would have registered as the second-deadliest pandemic in history. Australia managed to avoid the second wave entirely by walling itself off from the rest of the world, but the surprise third wave pierced the country’s defenses, and the terror and death that swept through its cities and towns was described as if it were the bubonic plague. Elsewhere, many who had been infected by the second wave got sick again in the third wave, but the disease was milder for them because they had partial immunity from their earlier exposure. Having been spared the second wave, Australians had no such protection.

Roughly a year and a half after it appeared, the pandemic finally subsided. The virus still lurked, but it infected people far less frequently, and those who did fall ill were more likely to survive. So many had already been infected that a degree of herd immunity had been achieved; there simply weren’t as many potential victims or as many potential spreaders. As American virologist Jeffery Taubenberger explained to Kolata: “A flu that is so freakishly perfect for killing people is far out on the edge of what is possible for influenza viruses, meaning that any mutations will make it less deadly.” It is a virus in “perfect balance,” Taubenberger said, “and it is a balance that will tip toward the more mundane type of flu with the tiniest nudge.” The virus had checkmated itself. That, rather than science and medicine, is what ended the 1918 pandemic.

This is not likely to happen with the novel coronavirus. Unlike flu viruses, it’s relatively stable. It mutates more slowly. And unlike the 1918 flu virus, in particular, the SARS-CoV-2 coronavirus is not the most efficient killer that a coronavirus possibly can be. The original SARS killed roughly 10 percent of its victims before testing, contact tracing, and isolation forced it into extinction, and MERS kills roughly 20 percent. Fortunately for the world, the coronaviruses that cause those diseases are much less transmissible than the youngest member of that murderous family.

While governments in 1918 failed largely through negligence and denial, medical scientists dedicated every waking moment to treating patients and searching for the pathogen so that they could develop a cure or vaccine. They failed heroically. Science simply hadn’t advanced far enough. Doctors weren’t sure if the disease was caused by bacteria or a virus, and viruses are so small that no one ever saw one until more than a decade later, with the invention of the electron microscope. Creating a vaccine back then wasn’t possible. Nature itself saved us—but only after running its course.

The novel coronavirus is not as deadly as the 1918 flu virus, but it could still kill millions of people. The difference is that this time we are willing—and able—to fight back.

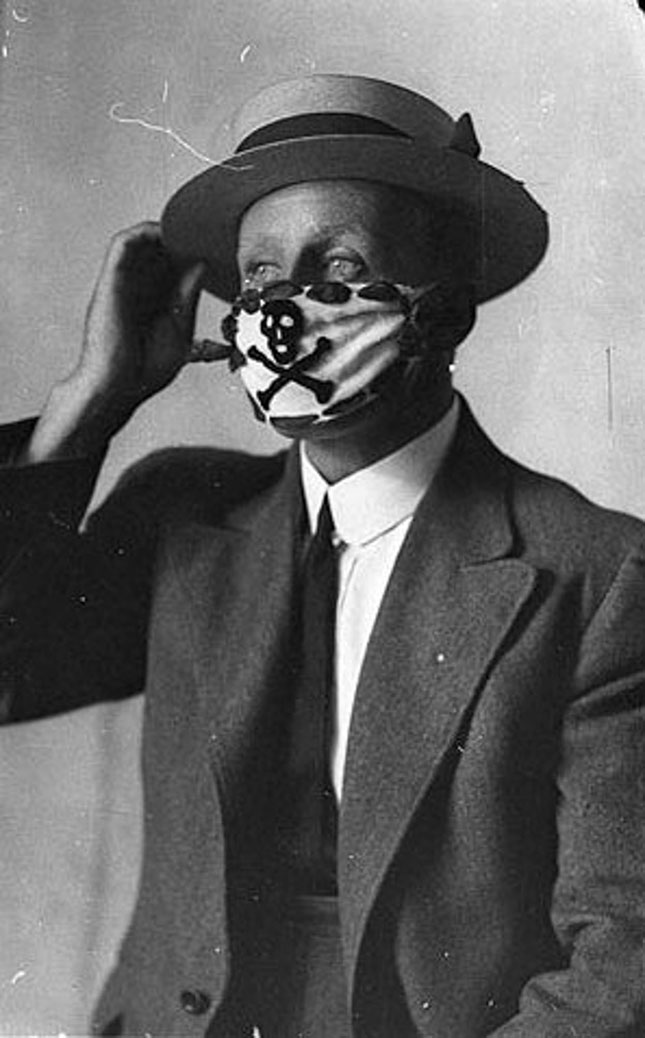

Top Photo: Between 50 million and 100 million people—as much as 5 percent of the world’s population at that time—were killed by the 1918 H1N1 flu pandemic. (MCCOOL/ALAMY STOCK PHOTO)

No comments:

Post a Comment