And yet, among the categories of federal statistics that are cynically crafted to deceive and manipulate the public to support advocacy for growth of programs, there is a category that is even worse than “poverty,” and that is the category of “food insecurity.” The “food insecurity” statistics do not come from the Census Bureau, but rather from another agency, the Department of Agriculture. Those are the people who administer the various federal food programs, like the Supplemental Nutritional Assistance Program (“SNAP”, aka food stamps), the Women, Infants and Children Program (“WIC”), and others. At the DOA, they have taken the art of creating fake statistics that can never improve no matter how much is spent to a whole new level.

Just the News has the scoop in a story dated October 26: “Bidenomics Boomerang: Hunger explodes on Joe’s watch as 10 million more fall into food insecurity.” Excerpt:

The number of Americans suffering from hunger and food insecurity exploded by more than 10 million under President Joe Biden, according to a U.S. Agriculture Department report this week that provided fresh evidence of inflation‘s impact of a basic staple of life. The report found 44.2 million Americans were living in food-insecure households in 2022, compared to 33.8 million the year before. “From 2021 to 2022, there were statistically significant increases in food insecurity and very low food security for nearly all subgroups of households described in this report,” USDA [sic] reported Wednesday.

More than 10 million households, and a more than 30% increase in the number of households, represents quite a huge one-year jump in this measure of “food insecurity.” JTN mentions inflation as a contributing factor, and likely that has something to do with the increase. But what is this statistic actually measuring? JTN takes the opportunity to bash Biden about hunger supposedly exploding on his watch. But does “food insecurity” really have anything to do with hunger?

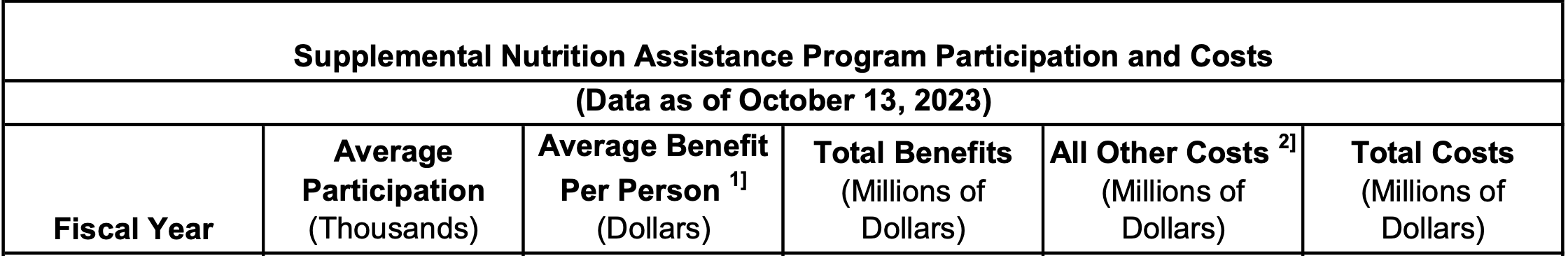

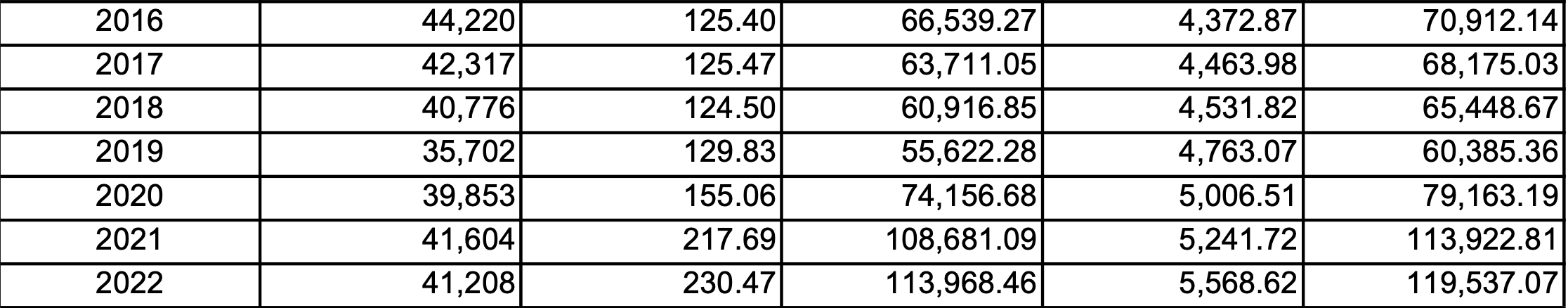

Probably your first instinct will be to infer that for “food insecurity” to increase so much there must at least have been some big decrease in the government benefits intended to address the issue. Boy would that be wrong. In fact, the first two years of Biden saw an incredible explosion of spending on the programs intended to cure this affliction. Here are the data from the Department of Agriculture for the SNAP program number of beneficiaries and spending from 2016 (last year of the Obama administration) through 2022 (most recent year of data)

As you can see, during the Trump years (2017-2020) both the number of participants and spending went down substantially up to 2019, before rebounding in the pandemic year of 2020. Then, during the two Biden years of 2021 and 2022, the number of beneficiaries further increased (by about 5%) despite the fading of the pandemic and the low unemployment rate; and meanwhile the spending skyrocketed, from about $79 billion in 2020 to almost $120 billion in 2022 — an increase of over 50%.

And here we have the true scandal of the federal food programs and the supposed “food insecurity” measurement. How is it even possible for programs supposedly designed to address a problem to fail so completely? During years when spending designed to reduce food insecurity increased by more than 50%, the number of people deemed to be in food insecurity not only did not decrease, but increased by over 30%.

I think that the answer to the question is that the “food insecurity” statistic was cynically created from the beginning to be impervious to decrease no matter how much gets spent on food assistance. Despite ubiquitous references and claims that the “food insecurity” statistic has something to do with hunger (and even JTN falls for this in the quote above), in fact “food insecurity” has nothing explicit to do with hunger, and the questions in the questionnaire mention nothing about hunger. Instead, the measure of food insecurity, devised during the Clinton Administration in the 1990s, basically comes from the answer on a survey to this question: “We worried whether our food would run out before we got money to buy more.” Was that often, sometimes, or never true for you in the last 12 months? Some of the people who respond affirmatively to that may well have been hungry at some time during the period in question, but you have no way to determine how many, if any.

Somehow the number of people who give an affirmative answer to that question (44.2 million in 2022 according to the latest report) bears a remarkable resemblance to the number of beneficiaries of the food stamp program (41.2 million in 2022 according to the DOA data in the chart). While there is no way to know that they are the exact same people, one might very reasonably look at the two numbers and infer that the large majority of the recipients of food stamps answer yes to the food insecurity survey question. After all, the design of the food stamp program is that the beneficiaries get a monthly allocation that they must make last to the end of the month. Of course many of them spend the allocation early and run low at the end of the month. The incredible thing is that even with a near 50% increase in the monthly benefit level during the Biden years, the percentage of people who spend the money early does not go down, but rather up.

You would think that the disaster of seeing “food insecurity” go up by 30% despite a $40 billion jump in spending would bring loud demands from the public, or at least the Congress, for firing of the responsible bureaucrats and restructuring of the program to something that is effective. But that’s not how this works. In the great bureaucratic tradition, the failure of the big spending increase to ameliorate the problem will be used by the agency to demand another round of increases in spending and staff. This time, they will argue, the increase in spending will work. The way to succeed in your main goal — which is growing your budget and staff — is to fail, and the more spectacularly the better.

No comments:

Post a Comment