Jack Nicastro

Jack Nicastro  Amelia Janaskie

Amelia Janaskie  Ethan Yang

– March 4, 2021

Ethan Yang

– March 4, 2021

Covid-19 and the lockdowns that followed should have been a rude wake-up call that we are losing our appreciation for the power of economic freedom. Our government deciding who can and cannot work was a blatant attack on economic and personal freedom at the most intimate level. This contempt for the right to earn a living, however, has been a growing issue well before Covid-19. Our government has been deciding who can and cannot work for decades through the advent of occupational licenses, which legally bar individuals from offering a professional service without first passing through artificially-imposed barriers to entry. The public interest law firm Institute for Justice writes,

“All Americans deserve the opportunity to earn an honest living. Yet occupational licenses, which are essentially permission slips from the government, routinely stand in the way of honest enterprise. Without these licenses, workers can face stiff fines or even risk jail time.”

A person is not truly free if they are unable to provide a professional service to another consenting individual, provided they are not harming others. However, occupational licenses are a direct prohibition on an individual’s right to perform a service for a living. This is also a very recent innovation as the Reason Foundation reports,

“The percentage of the workforce that must obtain a license to work has grown from about 4.5 percent during the 1950s to over 20 percent today.”

The astronomical growth of the occupational licensing regime doesn’t just cover high knowledge professions like medicine and law, but virtually everything imaginable from hedge trimming to hair cutting. Reason writes,

“More than 1,000 occupations are currently regulated by the states. Children even need the government’s permission to run makeshift lemonade stands during their summer vacations.”

The growth of such a regime has come at the cost of people’s ability to make a living with their unique talents. That is because often, such laws are made to protect incumbent businesses from competition by legally requiring new entrants to the market to pass a series of requirements that are costly both in time and money. The Institute for Justice writes,

“The requirements for licensure, though, can be an enormous burden and often force entrepreneurs to waste their valuable time and money to become licensed. Additionally, these burdens too often have no connection at all to public health or safety. Instead, they are imposed simply to protect established businesses from economic competition.”

It is one thing to require doctors to attend medical school, it’s another thing to mandate that hairdressers and florists pass hundreds of hours of formal training before they can legally solicit a client. Reason highlights an example of how outrageous and malicious licensure laws are when they tell the story of a talented florist struggling to obtain a license in Louisiana:

“The licensing exam emphasizes such subjective criteria as whether flowers have been “picked properly,” arrangements have the “proper focal point,” or flowers are “spaced correctly.” No wonder the passage rate is less than 50 percent. So despite her proven talent, Shamille has been forced to forego floral work and find a job elsewhere.”

Such licensure laws not only crush the ability of individuals to make a living, but also hurt the community as a whole to the benefit of well-connected interests and their friends in the government. A report from the Brookings Institution explains that, although licenses are advertised to increase public safety and service quality,

“[b]y limiting access to many occupations, licensing imposes substantial costs: consumers pay higher prices, economic opportunity is reduced for unlicensed workers, and even those who successfully obtain licenses must pay upfront costs and face limited geographic mobility. In addition, licensing often prescribes and constrains the ways in which work is structured, limiting innovation and economic growth.”

The claim that these economic costs are justified by improved quality and safety is a dubious one at best. In fact, Reason documents multiple studies finding that increased regulation of professions in the 1970s and 1980s most often produced no change in quality and is almost always coupled by an increase in the price of the service provided.

A Closer Look

Aside from these disturbing anecdotes, there are ways to easily quantify the cost that occupational licensing imposes on those seeking them. For the purposes of our analysis, we will be investigating how many hours, days, weeks, months, or years certain licenses require – opportunity cost – as well as the upfront price of taking the required examination or application fee – accounting cost.

To set the stage, occupational licensing is an aspect of law which is handled on a state-by-state basis. As the Brookings Institute explains:

“Typically, licenses are required by state governments…The U.S. licensure system takes a variety of forms throughout the country, but typically a state regulatory board… will process license applications, handle renewals, and oversee compliance with licensing rules, among other activities.”

Below is a graph compiled on the number of occupational licenses on a state-by-state basis, ranked in ascending order, with data from CareerOneStop, sponsored by the U.S. Department of Labor.

As the most populous as well as the fourth most licensed state in the country, we have chosen to inspect the opportunity and accounting costs of licensing in California. Two sets of jobs are provided: one set of low-skilled occupations; the other of high-skilled ones. In the low-skilled set, we highlight the licensing costs faced by manicurists, electrologists, estheticians, barbers, and cosmetologists. In the high-skilled set, we include lawyers, registered nurses, optometrists, physicians, and psychologists.

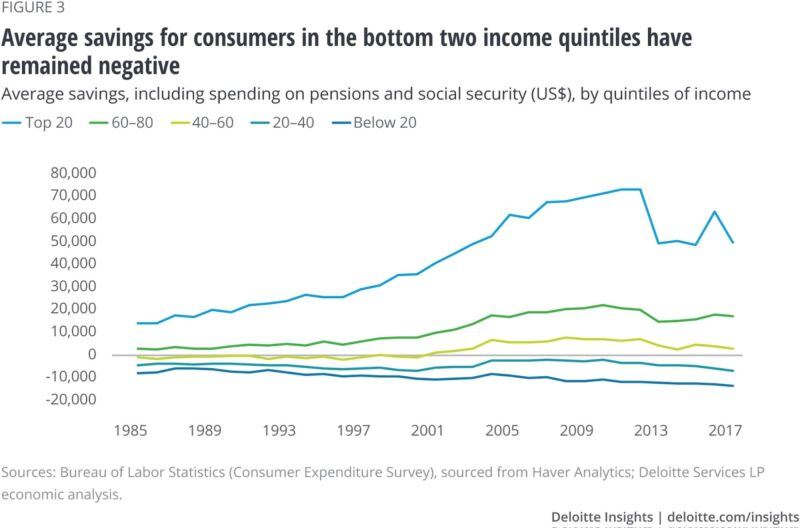

All along the spectrum of licensed professions, from high-skilled to low-skilled, the investment of time and money in obtaining legal permission to work is dizzying to consider. Even for manicurists, the low-skilled occupation with the lowest barriers to entry, one must accumulate 400 hours – the equivalent to 10 weeks of standard 9-5PM workdays – of unpaid apprenticeship and invest $110 before being able to legally bill for their services. While 10 weeks of unpaid labor might not seem like that big of a deal to a college student, for those in the bottom two quintiles of wage earners, i.e. most of those applying for a manicurist’s license, not working for 10 weeks and having to pay $110 can be financially impossible. According to Deloitte and research compiled by the Bureau of Labor Statistics, the bottom two quintiles of consumers in 2017 had negative savings, making unpaid labor and paying over one hundred dollars well nigh impossible.

Considering that this is the grim reality faced by those aspiring manicurists, the hurdles and hoops other beauticians must jump through to get their licenses only gets more difficult. Given these data, it is not surprising that a Reason Foundation study found that

“Licensing decreases the rate of job growth by an average of 20 percent.” The same study also found that the “cost of licensing regulations is estimated at between $34.8 billion and $41.7 billion per year,” meaning that the deadweight loss of complying with regulations is roughly equivalent to Armenia’s 2020 GDP of $40,788, as estimated by the International Monetary Fund.

While many intuit the blatant, undisguised regulation capture in the beauty fields, others believe that, while regulations may be unjustifiable in fields that do not involve life or death decision-making, they must be applied to high-risk fields. Whether consciously or not, most of us buy into the idea that to exist in a world where unlicensed physicians are commonplace would be uncertain, chaotic, and even dangerous. Provided this pervasive attitude, the subsequent graph detailing the time and financial investment required to become a trained medical professional or lawyer will be less shocking, prima facie, than the lower-skilled occupations.

The cost does not include an undergraduate and graduate education which could reach into six-figure levels when considered. For these high-skilled occupations, the investment of time is measured in years rather than hundreds of hours, and the cost of test-taking and licensing fees measures easily above the $125 of the sample low-skilled jobs, climbing well into the thousands. While extensive training, vetting, and ratings of professionals in these high stakes fields are crucial to consumer protection – certainly much more so than with the low-skilled jobs listed – the imposition of attending an undergraduate program before proceeding to graduate school to study the skills relevant to the vocation is artificial, expensive, and unnecessary.

Mandatory Licenses Do Not Improve Safety

According to an article by the The Regulatory Review, a publication associated with the University of Pennsylvania, an Obama Administration report found that although there may be reason to believe that licenses may improve safety in specific professions,

“[a]ccording to the federal report, however, studies on licensing requirements have found that licensing does not actually improve public health and safety. In its survey of twelve studies, the report identified only two that found that stricter licensing requirements increased the quality of services.”

The report also found that state licensing regimes reduce labor mobility and could become problematic as the prevalence of telework increases. Furthermore, these licensing regimes disproportionately exclude certain populations from the workforce such as those convicted of felonies, who would be well-served by meaningful employment, and even immigrants who possess certification from their country of origin but not from their state of residence.

Medical professionals, for example, are generally only licensed to practice in a given state, even after their years and years of rigorous training, and must jump through more hoops to practice elsewhere. Such restrictions on work only serve to preserve the market power of well-connected businesses via the coercive arm of the state. The illegitimacy of such licensing laws was revealed when former Vice President Mike Pence issued a regulation in the early days of the pandemic on March 18th, permitting all medical professionals to practice anywhere in the United States in light of limited medical workers and the threat of the coronavirus:

“With regard to medical personnel, at the President’s direction, HHS is issuing a regulation today that will allow all doctors and medical professionals to practice across state lines to meet the needs of hospitals that may arise in adjoining areas.”

Like many regulations that were lifted for emergency reasons during the age of Covid-19, restrictions on the ability of doctors to practice medicine across state lines without a license for each state was found to be unnecessary. When push comes to shove, it turns out a doctor can perform just as well in Connecticut as New York without extra certification. Go figure.

Society Can Do Without Mandatory Licenses

It is clear that many professions have not seen any noticeable increase in quality due to the advent of licenses and that such restrictions function primarily to reduce competition for established actors. Trimming hedges and styling hair for compensation without the prescribed training and certifications should not be an illegal act. The only people who benefit from this are the incumbent businesses that are protected from competition and disruptive innovation. Even highly sophisticated professions like law and medicine would be better off if such legal barriers were removed.

American legal scholar and attorney, Tim Sandefur, explains in his book The Right to Earn a Living that one of the biggest quality assurances is competition. The reason why you won’t encounter an unqualified professional at hospitals and law firms is due mostly to their motivation to provide excellent service rather than legal barriers set by the government. Take a look at any large law firm. They predominantly employ graduates exclusively from the top law schools. Not only that, but they typically hire those with the highest GPAs and strong extracurricular leadership positions. Passing the bar is the least of the requirements to work at such firms. Competition and innovation from both employees and employers is what raises standards, not mandatory licenses and state intervention.

Quality certifications are good to have but they shouldn’t be mandatory, especially if the cost of obtaining them is prohibitively expensive. Continuing with the example of the bar exam, passing is legally required to obtain a license to practice law. Although it is surely a good quality assurance test, it shouldn’t be illegal for someone to voluntarily solicit services from someone who hasn’t passed the bar. Skills come in all forms and perhaps some people can’t translate their legal talents into a test like the bar exam. Some people simply can’t afford a fully certified lawyer and they should have every right to solicit services from someone who isn’t.

Furthermore, what constitutes the practice of law or other sophisticated professions is often nebulous on purpose to keep out competition of all sorts. Supreme Court Justice Neil Gorsuch writes in his book A Republic If You Can Keep It, that

“[i]n recent years, lawyers have used these rules to combat competition from outsiders seeking to provide routine but arguably “legal” services at low or no cost to consumers.”

He cites cases involving innovative firms like Quicken Family Lawyer and Legal Zoom which were both sued in Texas and South Carolina, respectively. Their crime was providing what can be interpreted as a legal service. That service was selling software that helped draft documents like wills and contracts. Such a service is clearly beneficial to society, especially to those who can’t afford a lawyer to accomplish these necessary but relatively simple tasks.

Furthemore, the cost of going to law school is skyrocketing, much of which can be attributed to legal accreditation requirements. Justice Gorsuch notes that since the 1980s the cost of a private law degree has increased over 150% and a public degree over 420%, adjusted for inflation. Harvard Law School’s estimated cost of attendance is just shy of $100,000, $65,000 of that being for annual tuition, with three years being the average time it takes to receive a JD. That cost is relatively consistent among most elite law schools. Justice Gorsuch notes that the average tuition for an ABA accredited law school in the state of California is not much better at around $44,170 a year.

Again, not only are legally mandated certifications to work inflating the costs of important services, but they often keep it that way with little improvements to public safety. The legal profession is a clear example of a sector that certainly needs qualified workers. However, it is clear that mandatory requirements to even practice law in any form, whether it be complex corporate litigation or showing a family how to write a will, are not necessary. In fact they are clearly barriers to entry to the benefit of entrenched economic interests, at the expense of society.

You can apply the same level of analysis to any other complex profession such as medicine or accounting. All mandatory licenses do is take the power to offer and seek a service from the people to place it in the hands of the few. Even if someone is supposedly unqualified to offer a service, it is the right of the consumer to take that risk as it is likely they have no better option. If necessary, fraud and harm caused by incompetent or competent professionals can be punished via the criminal code.

Key Takeaways

Occupational licensing is one of those topics that may not seem like a big deal to the average person at first glance. Of course professionals should be qualified for their jobs and of course certifications provide a great way to ensure quality. The problem comes when the power to decide who can and who cannot work is given to a coercive authority. In the marketplace, bad actors are naturally corrected by competition and public scrutiny. This is especially true in our age of instant communication and crowd-sourced reviewing platforms such as Yelp. However, under our current occupational licensing regime, honest and hard working people are kept from offering a service to society by an arbitrary system that protects established businesses from competition. Such laws are built more so on fearmongering than a true concern for public safety. Furthermore, such a system artificially suppresses those who have the skills but lack the resources to fulfill the expensive and demanding licensure requirements set by the state.

While the number of occupational licenses increases, we have seen little increase in public safety as a direct result and a massive increase in prices. There is nothing more Un-American and Anti-Capitalist than a system that ordains some with the right to earn a living and bars others from that same essential right. Rather than cultivating an environment where everyone can safely contribute, occupational licenses have made the economy a pay-to-play scheme that only serves well-connected interests.

No comments:

Post a Comment