Five years ago, I shared this video explaining why trade deficits generally don’t matter.

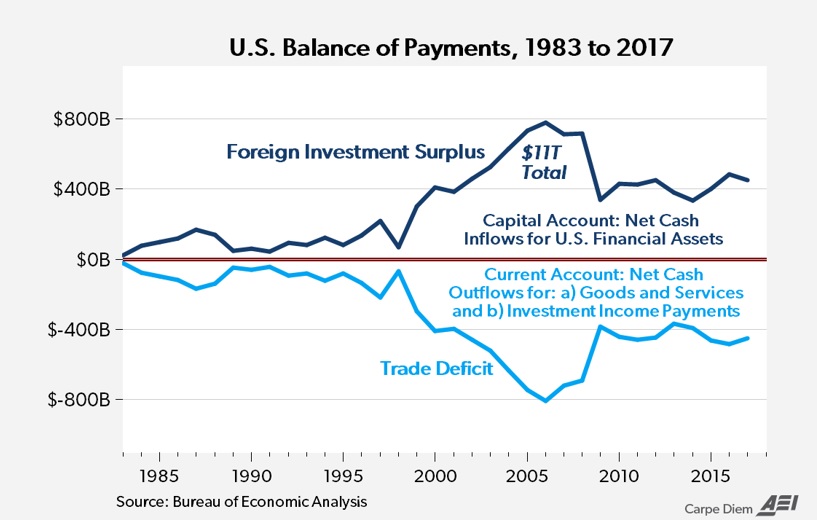

The most important thing to understand is that a trade deficit is the same thing as a financial account surplus (formerly known as a capital surplus), which is easy to understand when reviewing this graph.

And that type of surplus occurs when foreigners obtain dollars (by selling to Americans) and then decide that the best use of that money is to invest in the U.S. economy.

That’s generally a sign of a country’s economic strength.

Unfortunately, some people don’t grasp this relationship. And that leads them to supporting misguided ideas, such as protectionist trade restrictions.

Usually that means politicians directly imposing higher taxes on imports, as we’ve seen from Trump and Biden.

But sometimes they want an indirect approach. For instance, one of Trump’s main advisers wants to weaken the dollar. In a column for Forbes, Christine McDaniel explains why this is a very foolish idea.

Robert Lighthizer, a former U.S. trade negotiator and a potential Treasury Secretary pick for a second Trump administration, is reportedly discussing ways to devalue the dollar in order to reduce the U.S. trade deficit. But…a devaluation is a cut in a nation’s standard of living. …

Currency devaluation might sound like an appealing way to trim the trade deficit: All else equal, weakening the U.S. dollar would make U.S. exports cheaper, imports more expensive, and potentially reduce the trade deficit. But all other things don’t remain constant in such scenarios, and devaluing your own currency ends up having the opposite intended effect. It makes the economy less competitive and less efficient. … Anything the United States would gain through a devaluation in terms of cheaper exports, it would lose through its relatively pricier imports. Raw materials, intermediate goods, and capital goods comprise over half of U.S. imports. …

So, either American consumers and businesses would face higher prices here at home, U.S. exports would become less competitive, or a bit of both. …Currency devaluation is a race to the bottom that you can’t win. You might be able to get quick hits on the board in the immediate term, but within months, those are inevitably followed by punishing penalties.

Catherine Rampell of the Washington Post makes similar points in her column.

Trump’s policy team is reportedly scheming to devalue the U.S. dollar. …Trump’s objective…is to boost U.S. exports and reduce imports. Basically, if a dollar buys, say, fewer euros or Japanese yen than it currently does, that makes U.S.-made products look a little cheaper and potentially more attractive to European and Japanese customers (among others). …

That is, until you consider everything else that might happen if we deliberately tried to weaken our currency… how would Team Trump weaken our currency? That’s not totally clear. He might try to force the Federal Reserve to cut interest rates. …a weaker dollar would likely lead to higher prices for American consumers… So much for Trump’s pledge to vanquish inflation.

Both of these columns make good points, but they’re understating the main argument. What everyone needs to realize is that devaluation is inflation.

And presumably there’s no need nowadays to explain why inflation is bad, considering the damage caused when central banks decided to devalue currencies during the pandemic.

Moreover, it’s a bad policy that won’t work. Because once the Fed’s easy-money policy leads to rising prices, that will boost the cost of American-produced goods.

So the long-run impact may be a higher trade deficit.

P.S. Ms. Rampell makes another observation that deserves attention.

Deliberately weakening the dollar, or even attempting to, also threatens its role as the world’s “reserve currency.”

If you want to know more about that issue, click here.

No comments:

Post a Comment