October 29, 2022 by Dan Mitchell @ International Liberty

As part of “European Fiscal Policy Week,” I’ve complained about bad Italian fiscal policy, bad Europe-wide fiscal policy, bad British fiscal policy, and also the unhelpful role of the European Union.

But I want to end the week on an optimistic note, so let’s take a look at Switzerland‘s spending cap.

Known as the “debt brake,” the rule was approved by 84.7 percent of voters back in 2001 and took effect with the 2003 fiscal year.

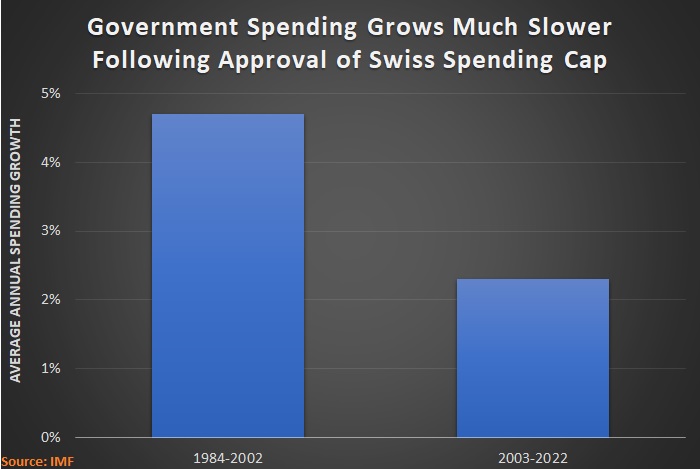

And if you want to know whether it has been successful, here’s a comparison of average spending increases before the debt brake and after the debt brake.

The above data comes directly from the database of the IMF’s World Economic Outlook.

There are some caveats, to be sure.

- The IMF data cited above is not adjusted for inflation, though inflation has not been a problem in Switzerland.

- The IMF numbers also show total government spending rather than just the outlays of the central government, but most cantons also have spending caps.

The bottom line is that Swiss fiscal policy dramatically approved after the spending cap took effect.

Switzerland’s Federal Finance Administration has a nice English-language description of the policy.

The debt brake is a simple mechanism for managing federal expenditure. …Expenditure is limited to the level of structural, i.e. cyclically adjusted, receipts. This allows for a steady expenditure trend and prevents a stop-and-go policy. …The debt brake has passed several tests since its introduction in 2003…

The binding guidelines of the debt brake helped to swiftly balance the federal budget when it was introduced. The debt brake prevented the high tax receipts from the pre-2009 economically strong years from being used for additional expenditure. Instead, it was possible to build up surpluses and reduce debt. …s public finances are well positioned when compared internationally. Aside from the Confederation, most of the cantons have a debt brake too.

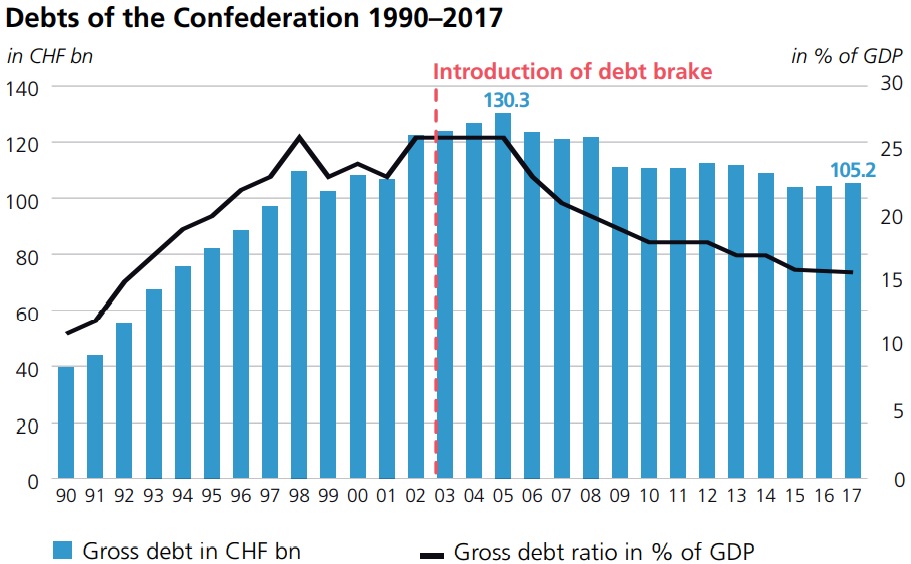

Here’s a chart from the report. It shows that debt is on a downward trajectory, especially when measured as a share of economic output (the right axis).

For what it’s worth, I’m glad the debt brake reduced debt, but I care more about controlling government spending. That being said, the Swiss spending cap also is a success on that basis.

The burden of spending as a share of GDP was increasing before the debt brake was approved. And since 2003, it’s been on a downward trajectory.

Here’s what Avenir Suisse, a Swiss think tank, wrote back in 2017.

Since the early 2000’s, Switzerland’s fiscal institutions have been successful in keeping the overall levels of taxation and spending at moderate levels. The country’s high fiscal strength is based on…Switzerland’s debt brake, a key institutional mechanism for managing public finances which subjects the Confederation’s fiscal policy to a binding rule…and contributes significantly to the country’s fiscal discipline. …

Switzerland’s spending cap has helped the country avoid the fiscal crisis affecting so many other European nations. …The Swiss debt brake is the ideal model for other countries lacking fiscal discipline to embrace. …

The Swiss debt brake’s most important contribution, however, cannot be measured in figures… In the early 1990s fiscal policy was oriented more towards the demands of the public sector…

Today, however, the administration, the government and the parliaments believe it is self-evident that expenditures must develop in the medium term in line with revenue. Fiscal federalism, as an important element in the cantons, protects against overcrowding access to the tax side.

That last sentence deserves some elaboration. The authors are noting (“overcrowding access to the tax side”) that it is possible to increase spending by increasing taxes, but that’s not an easy option in Switzerland because voters can use direct democracy to reject tax hikes (as they have in the past).

P.S. The Debt Brake has an opt-out clause that allows more spending in an emergency. And, during the pandemic, spending did jump by more than 12 percent in just one year. But there’s also a claw-back provision that requires lawmakers to be extra frugal in subsequent years. And that policy seems to be successful. The big spending surge in 2020 was followed by two years of zero spending growth (with another year of no spending growth projected for 2023).

P.P.S. Look at this map if you want to see how much better Switzerland is than the rest of Europe.

P.P.P.S. Look at these charts if you want to see how Switzerland is doing better than the United States.

No comments:

Post a Comment