I have a three-part series on why price controls are misguided (here, here, and here). In this clip from a recent appearance on Vance Ginn’s Let People Prosper, I look at the specific example of price controls on late fees.

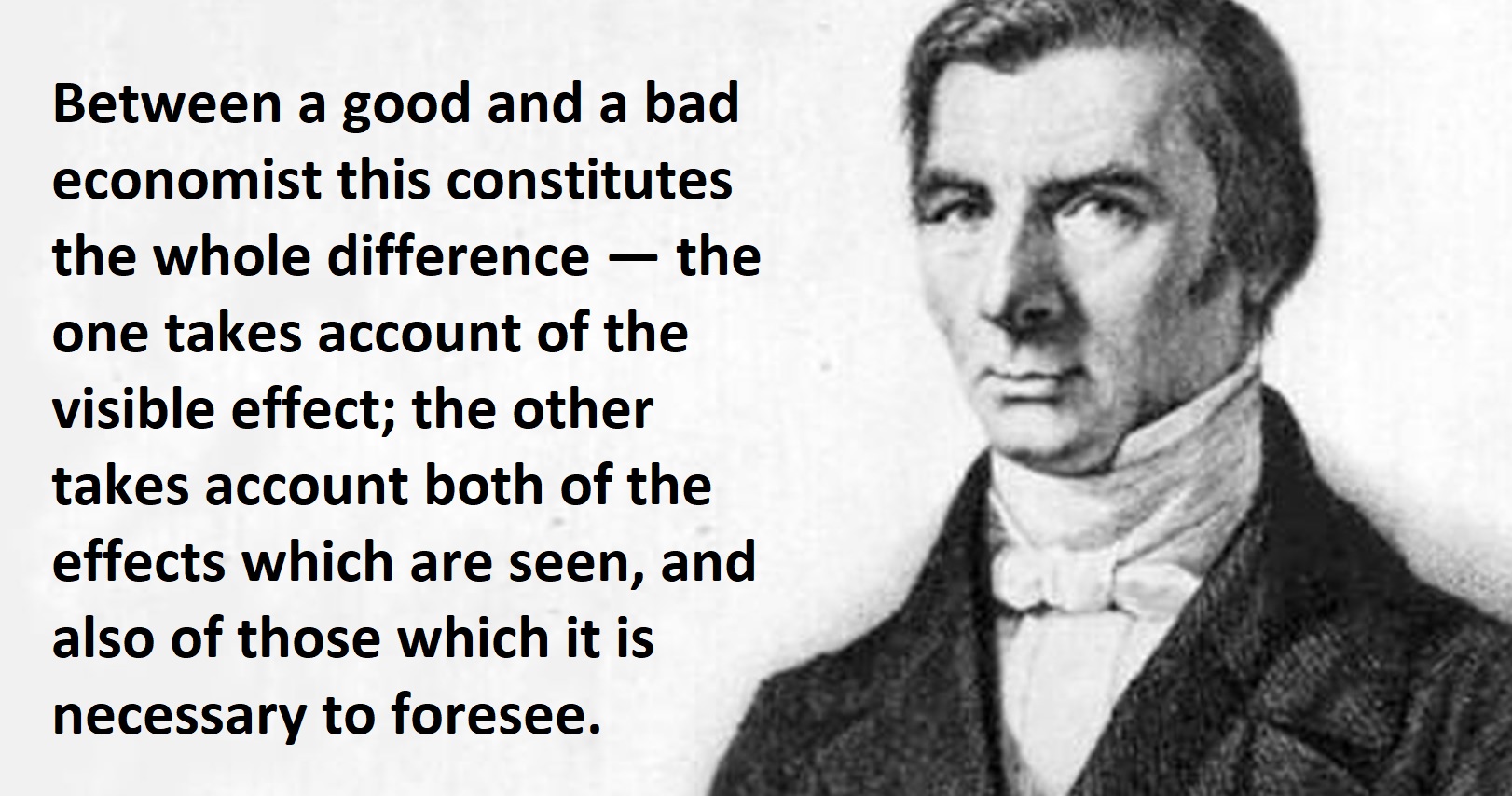

While I think my points are sound, I confess they are not original.

I’m simply recycling the wisdom of Frederic Bastiat, who succinctly and accurately explained way back in the 1800s that you can’t analyze an issue without considering the secondary effects (the “unseen”).

In this case, limiting late fees on credit cards will lead to negative effects in other areas.

I’m not the only one to make this point. The Wall Street Journal editorialized about this issue a few days ago. Here are some excerpts.

If Americans see their credit costs increase, access to credit decline, or card rewards disappear, blame the Administration’s new price controls. The Consumer Financial Protection Bureau (CFPB) last week finalized a rule effectively capping credit-card late fees at $8… Yet as even the CFPB acknowledges, the lower penalty may cause more borrowers to pay late, and as a result incur higher “interest charges, penalty rates, credit reporting, and the loss of a grace period.”

This would make it harder to qualify for an auto loan or mortgage. The agency concedes that credit-card issuers may also raise interest rates, reduce rewards, “increase minimum payment amounts or adjust credit limits to reduce credit risk associated with consumers who make late payments.” Because some states cap credit-card interest rates, “some consumers’ access to credit could fall.”

Thanks, Mr. President. By the way, the rule comes as credit-card delinquencies have risen to the highest level in more than a decade. …The Biden Administration is playing up its price controls as an election-year gambit, but it never explains the unseen effects down the road. The forgotten man always pays.

By the way, the editorial includes this bit of bad news caused by a different example of financial intervention.

Consumers are the biggest losers, as we’ve learned from other such price controls. The Durbin Amendment to Dodd-Frank directed the Fed to limit fees charged to retailers for debit-card processing. A 2017 Federal Reserve staff study found that as a result larger banks reduced free checking and raised minimum balance requirements. Small banks not subject to the cap also limited free checking because they faced less competition. Rather than lower prices, retailers pocketed the savings.

And I wrote earlier this year about another example of the Biden crowd imposing red tape on the financial services industry.

The bottom line is that more government is only the answer if you’ve asked a very strange question.

No comments:

Post a Comment