Before our

depressing discussion today about the fiscal impact of entitlement programs (Social Security, Medicare, Medicaid, EITC, Food Stamps, welfare,

and Obamacare,

etc), here’s a video of how it all began.

I think this is

a great introduction to the issue, particularly since you learn how “public choice”

(i.e., politicians engaging in self-serving behavior) played a key role in the

development of today’s welfare state.

But if you

don’t have the time to watch a long video, here are four key things to

understand.

Entitlements (budget geeks sometimes use the term “mandatory spending”) are programs that automatically give people money if they meet certain requirements (such as reaching a certain age or having income below a certain level).

Since these

programs automatically give people money, they are not part of

the annual appropriations process (the “discretionary

spending” parts of the budget that are determined on a yearly

basis).

Some

entitlement programs are “means tested” and designed to funnel money to

low-income individuals. This type of spending is sometimes referred to as

“unearned benefits.”

Some

entitlement programs are “social insurance” since people pay specific tax in exchange

for specific benefits. This type of spending is sometimes referred to as

“earned benefits” (though in many cases recipient

receive much more than they paid).

By the way,

there’s one additional thing to understand.

Indeed, it may

be the most important thing to understand if you care about America’s fiscal

and economic future.

5. Entitlement

programs are a slow-motion

fiscal train wreck.

Let’s look

at a new study authored

by James Capretta of the America Enterprise Institute. He also has some

sobering observations on the history of entitlement programs.

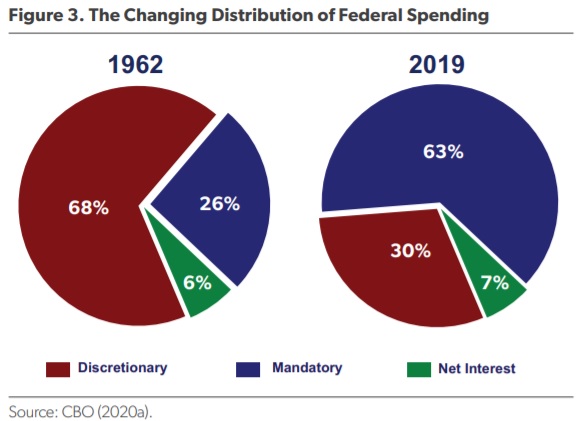

The growing expense of entitlement programs has occurred steadily for more than a half century and is reflected in the shifting distribution of federal spending activity. …by the early 1960s, two-thirds of all spending continued to require approval by the House and Senate appropriations committees each year, and less than a third was spent on entitlement programs. … By 2019, nearly two-thirds of all spending in the budget was for entitlement programs, and less than a third went to annually appropriated accounts.

While there are

dozens of entitlement programs, the big three are Social Security, Medicare,

and Medicaid.

The largest entitlement programs are Social Security, Medicare, and Medicaid. Together, they now make up nearly half of all federal spending. Their combined growth over the past half century is the primary source of intensifying fiscal pressure. …In 2019, combined federal spending on them was 9.8 percent of GDP, up from 3.7 percent in 1970. CBO expects them to cost 17.2 percent of GDP in 2050, which is almost equal to the average annual revenue collected by the federal government from 1970 to 2019.And here’s how they’ve been consuming ever-larger shares of America’s economic output.

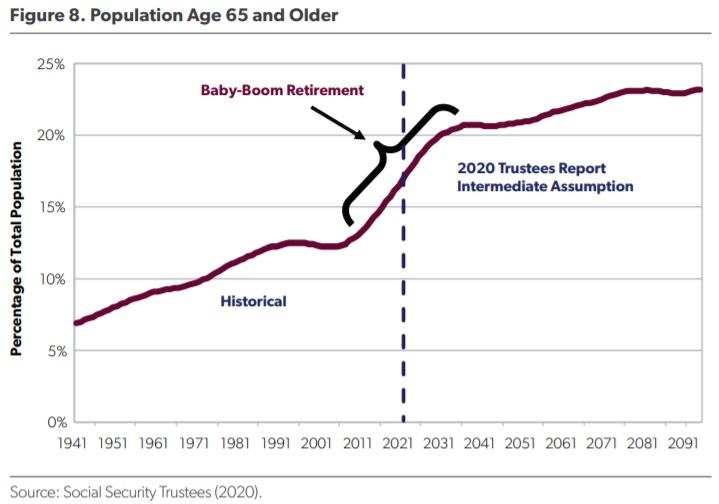

What’s driving this ever-increasing fiscal burden? In part, it’s because we have more and more old people and they are living longer.

So what does

all this mean?

Capretta points

out that uncontrolled entitlement spending may lead to a debt crisis.

I don’t

disagree, but I think that’s a secondary concern. The real problem is that

government spending will become an ever-larger economic burden. And that will

hinder growth whether it’s financed by borrowing or taxes.

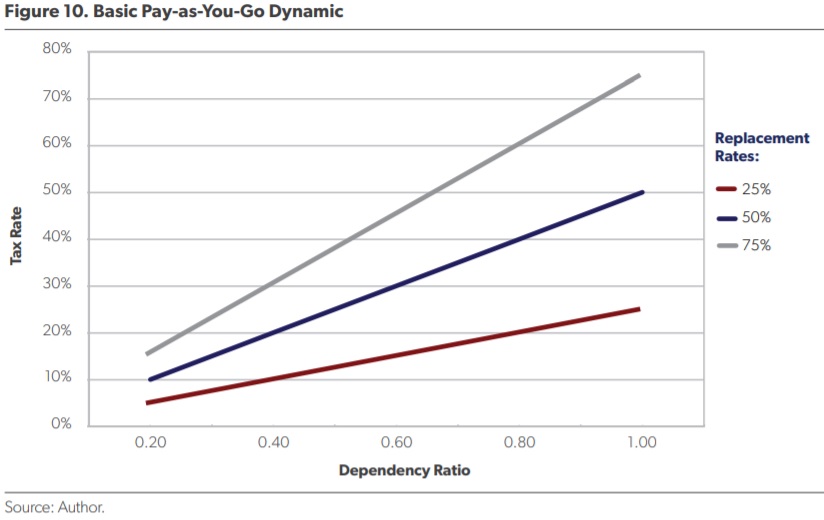

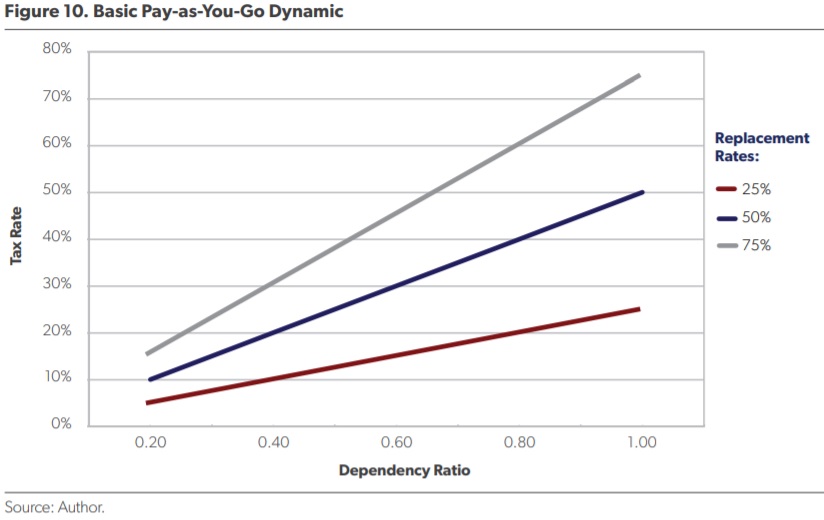

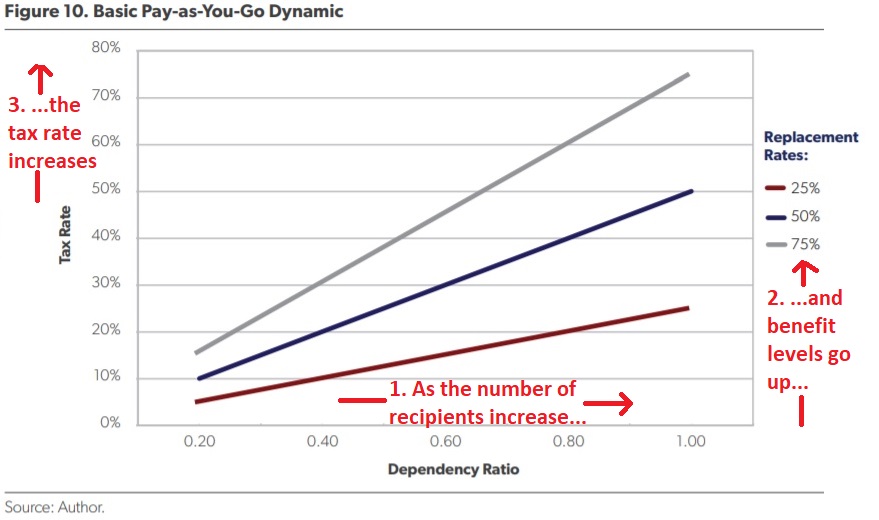

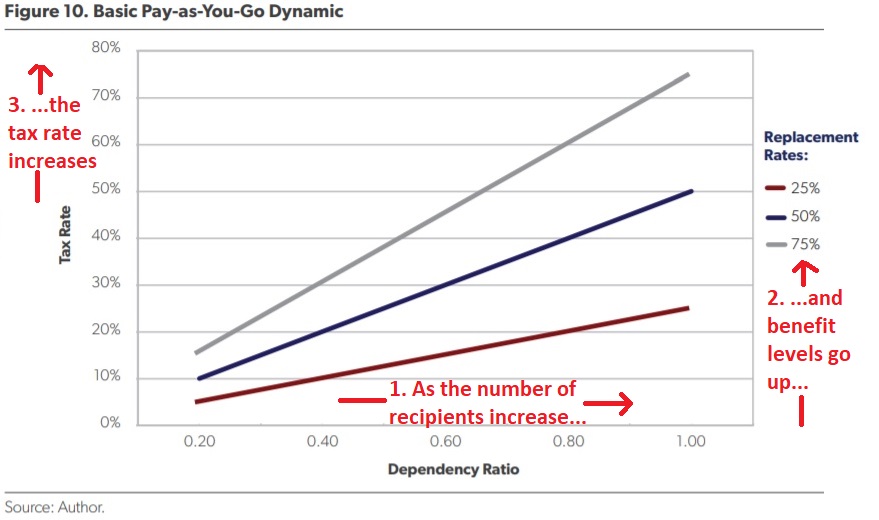

Speaking of

taxes, here’s the chart from the study that deserves our close attention. It

shows the relationship between demographics, benefit generosity, and tax

burdens.

Here’s how

Capretta describes the relationship.

…for each of the stipulated replacement rates (25, 50, and 75 percent), the tax rate necessary to keep the program solvent rises with increases in the aged dependency ratio. This explains why social insurance taxes in many aging societies have been increased to high levels in recent decades.

I’ve taken the

liberty of augmenting the chart to show how these factors interact (though the

order of #1 and #2 doesn’t matter).

The bottom line

is that the United States is on track to become a high-tax, European-style welfare

state if fiscal policy is left on autopilot.

In other words,

unless there’s genuine

entitlement reform, future Americans will be condemned to lower

living standards.

P.S. Here’s

some more history. In a column for

the American Institute for Economic Research, Richard Ebeling looked at British

history to explain how the private sector played a role in social insurance

before being displaced by government.

Throughout the 19th century, a primary means for the provision of what today we call the “social safety nets” was by the private sector outside of government. The British Friendly Societies were mutual assistance associations that emerged to provide death benefits for the wives and children of the breadwinner who had passed away. But they soon offered a wide array of other mutual insurance services, including health care coverage, retirement pension programs, unemployment insurance, savings clubs to purchase a family house, and a variety of others. …by the end of the 19th century around two-thirds to three-quarters of the entire British population was covered by one or more of their programs and insurances. The research also discovered that a large majority of the subscribers were in the lower income brackets of the time… What stands out is that these were all private and voluntary associations and exchanges, in which the government paid little or no role.

On a related

note, here’s an excellent

short video on the English “poor laws” from the 1800s.

P.P.S. In

addition to the fiscal burden of entitlement programs, there’s also a major problem in

the way these programs discourage work.

No comments:

Post a Comment